Mehmet Sebih Oruc, Newcastle UniversityIt feels like there are so many things constantly vying for our attention: the sharp buzz of the phone, the low hum of social media, the unrelenting flood of emails, the endless carousel of content. It’s a familiar and almost universal ailment in our digital age. Our lives are punctuated by constant stimulation, and moments of real stillness – the kind where the mind wanders without a destination – have become rare. Digital technologies permeate work, education, and intimacy. Not participating feels to many like nonexistence. But we tell ourselves that’s OK because platforms promise endless choice and self-expression, but this promise is deceptive. What appears as freedom masks a subtle coercion: distraction, visibility, and engagement are prescribed as obligations. As someone who has spent years reading philosophy, I have been asking myself how to step out of this loop and try to think like great thinkers did in the past. A possible answer came from a thinker most people wouldn’t expect to help with our TikTok-era malaise: the German philosopher Martin Heidegger. Heidegger argued that modern technology is not simply a collection of tools, but a way of revealing – a framework in which the world appears primarily as a resource, including the human body and mind, to be used for content. In the same way, platforms are also part of this resource, and one that shapes what appears, how it appears, and how we orient ourselves toward life. Digital culture revolves around speed, visibility, algorithmic selection, and the compulsive generation of content. Life increasingly mirrors the logic of the feed: constantly updating, always “now” and allergic to slowness, silence and stillness. What digital platforms take away is more than just our attention being “continuously partial” — they also limit the deeper kind of reflection that allows us to engage with life and ourselves fully. They make us lose the capacity to inhabit silence and confront the unfilled moment. When moments of silence or emptiness arise, we instinctively look to others — not for real connection, but to fill the void with distraction. Heidegger calls this distraction “das man” or “they”: the social collective whose influence we unconsciously follow. In this way, the “they” becomes a kind of ghostly refuge, offering comfort while quietly erasing our own sense of individuality. This “they” multiplies endlessly through likes, trends, and algorithmic virality. In fleeing from boredom together, the possibility of an authentic “I” disappears into the infinite deferral of collective mimicry. Heidegger feared that under the dominance of technology, humanity might lose its capacity to relate to “being itself”. This “forgetting of being” is not merely an intellectual error but an existential poverty. Today, it can be seen as the loss of depth — the eclipse of boredom, the erosion of interiority, the disappearance of silence. Where there is no boredom, there can be no reflection. Where there is no pause, there can be no real choice. Heidegger’s “forgetting of being” now manifests as the loss of boredom itself. What we forfeit is the capacity for sustained reflection. Boredom as a privileged moodFor Heidegger, profound boredom is not merely a psychological state but a privileged mood in which the everyday world begins to withdraw. In his 1929 to 1930 lecture course The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics, he describes boredom as a fundamental attunement through which beings no longer “speak” to us, revealing the nothingness at the heart of being itself. “Profound boredom removes all things and men and oneself along with it into a remarkable indifference. This boredom reveals beings as a whole.” Boredom is not absence but a threshold — a condition for thinking, wonder, and the emergence of meaning. The loss of profound boredom mirrors the broader collapse of existential depth into surface. Once a portal to being, boredom is now treated as a design flaw, patched with entertainment and distraction. Never allowing ourselves to be bored is equivalent to never allowing ourselves to be as we are. As Heidegger insists, only in the totality of profound boredom do we come face to face with beings as a whole. When we flee boredom, we escape ourselves. At least, we try to.The problem is not that boredom strikes too often, but that it is never allowed to fully arrive. Boredom, which has paradoxically seen a rise in countries drowning in technology like the US, is shameful. It is treated like an illness almost. We avoid it, hate it, fear it. Digital life and its many platforms offer streams of micro-distractions that prevent immersion into this more primitive attunement. Restlessness is redirected into scrolling, which, instead of meaningful reflection, produces only more scrolling. What disappears with boredom is not leisure, but metaphysical access — the silence in which the world might speak, and one might hear. In this light, rediscovering boredom is not about idle time, it is about reclaiming the conditions for thought, depth, and authenticity. It is a quiet resistance to the pervasive logic of digital life, an opening to the full presence of being, and a reminder that the pause, the unstructured moment, and the still passage are not failures – they are essential. Mehmet Sebih Oruc, PhD Researcher in digital media and philosophy, Newcastle University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

How Digital Detox Can Boost Your Mental Health, Productivity At Workplace? (2025-07-08T11:59:00+05:30)

The concept of Digital Detox is something that is crucial in our fast-paced life. It can bring a healthier balance to our lives. In our world, where technology and work often blend into our personal time, it’s important to step back and find some peace away from screens and digital devices. This is what we call a ‘Digital Detox’. What is Digital Detox? So, what exactly is digital detox? It’s the practice of taking a break from technology and the digital world. Imagine turning off your phone, stepping away from your computer, and just being in the moment without any digital distractions. It’s about reclaiming those moments of calm and presence in our real, not virtual, lives. Why Is Digital Detox So Important These Days? Why is this important, you might ask? Well, in a world where we’re constantly connected to the digital world, we often forget to connect with ourselves and those around us. A digital detox helps us to relax, refocus, and reduce the stress that comes from being always ‘on’. It can improve our mental health, sleep, and overall well-being. How To Apply Digital Detox In Your Daily Life? Now, let’s dive into how we can manage this in our busy lives, especially at work. Here are some practical strategies. 1. Prioritize Your Tasks Firstly, prioritize and arrange your task list. It might seem old-fashioned, but a handwritten to-do list can work wonders. Break down big tasks into smaller, manageable ones and set clear goals. This helps to focus and get things done efficiently, bringing a sense of achievement. 2. Set Time Blocks Managing time effectively is another key step. Allocate specific time blocks for different tasks. It’s better to focus on one task at a time rather than juggling multiple things, which often leads to stress. 3. Declutter Your Mind Stress management is vital too. Practices like mindfulness, meditation, and yoga can significantly reduce stress. Regular exercise releases endorphins, which combat stress. Some companies, even arrange professional mindfulness sessions in their workplaces. 4. Collaborate With Others Collaboration at work helps too. Share responsibilities within teams, distribute workloads and don’t hesitate to ask for help when needed. It’s about working smart, not just hard. 5. Recharge Yourself Don’t forget to take breaks. Short breaks for a cup of tea, a quick game, or a quick productive talk can recharge your batteries and prevent burnout. Lastly, reflect and adjust. Regularly check what’s working and what’s not, and be open to changing strategies. Is It Compulsory To Follow Digital Detox Trend?Digital detox isn’t just a trend; it’s a necessity in our technology-driven world. It helps us to stay focused, reduce stress, and maintain a healthy balance in life. By adopting these strategies, we can all work towards a more balanced, healthier lifestyle.How Digital Detox Can Boost Your Mental Health, Productivity At Workplace? |

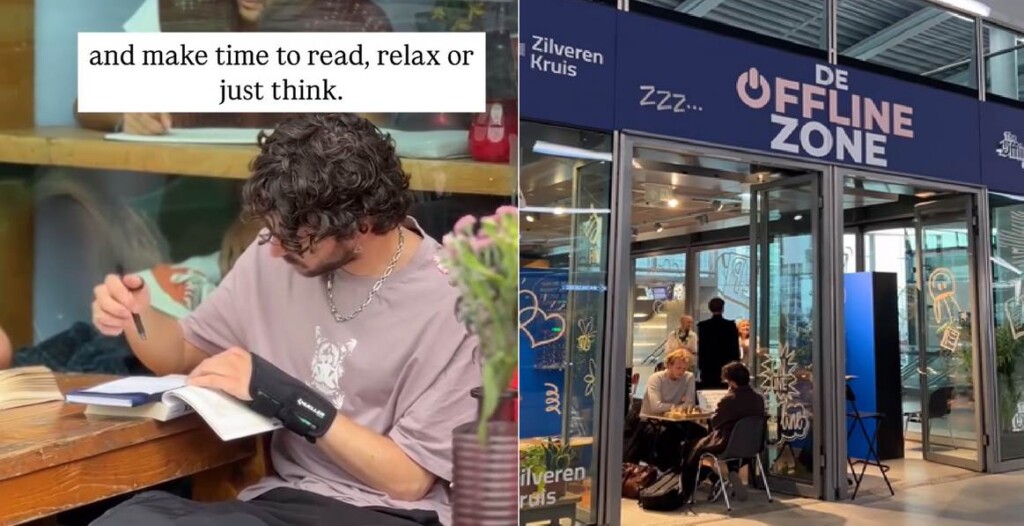

Young Adults Joining 'Offline Clubs' Across Europe–to Replace Screen Time with Real Time (2025-06-27T12:59:00+05:30)

– credit The Offline Club via Instagram – credit The Offline Club via InstagramNot everyone pines for the days without cell phones, but what about social media? Would you erase social media from the history books if you could? If you said yes, you share the feelings of a staggering 46% of teenage respondents to a recent survey from the British Standards Institution (BSI), which also found that 68% of respondents said they felt worse when they spend too much time on their socials. Despite often being seen as the most vulnerable generation to smartphone addiction and social media use, it appears teens, who in any generation are extremely quick to pick up emerging social trends, are picking up on the negative impact social media has had on their lives, and are enthusiastically looking to cut back. Enter The Offline Club, (who ironically have 530,000 followers on Instagram) a Dutch social movement looking to create screen-free public spaces and events in cafes to revive the time before phones, when board games, social interaction, and reading were the activities observed in public. They also host digital detox retreats, where participants unplug from not only their smartphones, but computers too, and experience a life before the internet. In a time when social media and mass, internet-enabled communication through text and video have allowed psychology and medical professionals to gain celebrity levels of influence, many of those same professionals, be it Jonathan Haidt or Dr. Phil McGraw, are sounding the alarm over the harm which the introduction of handheld internet access has had on the mental wellbeing of the youngest generations. BSI’s research showed that out of 1,290 individuals aged 16-21, 47% would prefer to be young in a world without the internet, with 50% also saying a social media curfew would improve their lives. Some countries, DW reports, are considering age restrictions on social media accounts. Australia has already implemented one at age 16. Cell phone bans at schools is becoming more and more common around the world, especially in the UK. The Offline Club is taking advantage of this rising cross-cultural awareness and helps its followers replace “screen time with real time.” Their founders envision a world where time spent in public is present and offline. It started in Amsterdam, but Club chapters quickly organized in Milan, Berlin, Paris, London, Barcelona, Brussels, Antwerp, Dubai, Copenhagen, and Lisbon. Anyone can start a club in a city. So long as they can register a business entity in their country, the Club provides training and branded material. Young Adults Joining 'Offline Clubs' Across Europe–to Replace Screen Time with Real Time |

Church donation box goes digital in Greece (2025-05-30T12:14:00+05:30)

ATHENS - Devout regulars attending Athens's main Roman Catholic church that honours a first-century saint have discovered a 21st-century update: Their donation box is now hooked up to a digital payments system. The addition of the Point of Sale (POS) device in the Cathedral Basilica of St Dionysius the Areopagite is the first in a Greek church, even though their use is common elsewhere, including in Africa. Such was the stir created in Orthodox-dominated Greece that cameras from national broadcasters were on hand Sunday, trained on the POS's small screen -- even though it was not yet switched on. The unit was expected to be working within a week, accepting card-tap donations as small as one cent, up to a limit of 1,000 euros ($1,130). It was sitting on a wooden furniture unit alongside prayer candles that could be exchanged for donations. "The first church donation box with POS: Tourists requested it, the Church made it happen", said an article on the protothema.gr news website. The cathedral's priest, Georgios Dangas, noted mildly that churches elsewhere in the Western world had been using POS units for decades. "We have been asked to install a POS by tourists coming to Athens. Worshippers from all over the world who travel without cash want to give something for the church," he told AFP. He added that the expenses of running the church, the salaries of the priests and the charity work are not paid by either the Greek state or the Vatican, so the contributions were vital. Sunday mass in the church is frequently attended by women from the Philippines who work in the homes of the rich who live in nearby upscale neighbourhoods. The POS device, which was hotly debated in Greece and on social media over the weekend, may find imitators in the Orthodox Church -- the most followed religion in Greece."The man who installed it told me that priests from Orthodox churches also contacted him. But they said let's see how it goes in the Catholic Church and then we'll see," the priest said. Church donation box goes digital in Greece |

In a world of digital bystanders the challenge is for all of us to design engaging online education (2025-05-20T13:13:00+05:30)

teven Warburton, University of New England; Muhammad Zuhdi, Universitas Islam Negeri Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta, and Stephen Dobson, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of WellingtonWe are increasingly becoming digital bystanders, continually monitoring our different palm-and-TV-sized screens. From dawn to dusk and even in moments of insomnia we turn to digitally communicated news and social media. In the world of education, from primary school to university and beyond, we have realised digital learning is not only an option for learning, but is fast becoming the main option. Consider this vignette: during the COVID-19 pandemic a family are living in a big city where access to stable digital streams and affordable data bundles is not a problem. Confined to long periods of school learning now moved online, one of the parents asked their daughter about her experience. She says:

She had became a digital bystander. The teacher struggled to engage with all students, and few experienced rich interactions with the teacher. In the digital world it is not simply about learning the skills (digital self-help manuals and videos are plentiful). Many teachers and professors still argue that a face-to-face experience is more authentic than digitally mediated learning. The growth of MOOCs (massive online open courses) in recent years has challenged this view. These have gained traction as both free educational offerings and significant business opportunities based on short courses. Time for a change of mindsetSo how do we accommodate this changing digital world? Historically, when railway travel arrived, looking at the world through a window as it sped by was an unnerving experience. So, too, was the fear of being part of or witnessing a railway accident. It took people time to catch up and change their mindsets. The same is true of digitally driven change in education. We cannot take time out from change. What is required is “reflection in action”, as Donald Schon put it, to work out how to adjust to changes. When we consider our vignette, how can we win the hearts and minds of students and teachers to ensure they both perceive and experience learning online as meaningful and transformative? Is this a question of challenging the traditional mindset described above? By exploring the ways in which face-to-face learning is translated into online learning, we can start to identify a series of approaches on a spectrum from simple technological substitution to more radical redefinitions of teaching. In this model of substitution, augmentation, modification and redefinition, we tend to find many educators remain firmly rooted in using technology to replace what they already do in the classroom. As a result, the human essence of the teaching experience is lost when mediated via a digital interface. An example here might be the distribution of electronic classnotes to replace the course textbook. The result is a learning setting that’s clunky compared to the day-to-day user experience of the internet. The mismatch exemplified here in the transition from the physical classroom to online is often not well managed. A learner’s experiences of the digital education space can be dramatically different to the seamless and frictionless user experiences of a social internet. Within a paradigm of replacement versus reinvention, we have a natural gap between the experiences of teachers and students. A need for inclusive design for onlineNeither better access to technology nor more training to use digital systems will bridge this gap. This is a design gap. In recognising this, the solution becomes more straightforward – there is an absolute need to “design for online”, as Cathy Stone persuasively argues. But this design cannot be the sole responsibility of the teacher. We need to bring together multiple perspectives and skills, including those of teachers, students and technologists, to co-design learning experiences. No longer is the teacher the sole voice of authority. All contribute: the teacher skilled in curriculum, the student understanding what it means to be supported and motivated to learn, and the technologist sharing modes of digital delivery. There are then no digital bystanders – all have agency as designers. As Herbert A. Simon once said, anyone who is engaged in “changing existing situations into preferred ones” is a designer. There is no global template for designing for online learning. Each time we come together – the teacher, student, technologist – we form a new community with a shared discourse. This is a reflective and democratic space that allows us to act with consideration and respect for the skills and knowledge of others. With historical hindsight, we will do well to reconsider what the railway journey offered: the ability to visually reflect upon and design a personal world without leaving the carriage. With the digital production of teaching and learning, we too are now called upon to reflect upon and design a world of learning without leaving our seat in front of a digital screen. Steven Warburton, Pro Vice-Chancellor Academic Innovation (Acting), University of New England; Muhammad Zuhdi, Adjunct Research Fellow Victoria University of Wellington; Head of the Quality Assurance Institute and Senior Lecturer, Universitas Islam Negeri Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta, and Stephen Dobson, Professor and Dean of Education, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

What is a ‘smart city’ and why should we care? It’s not just a buzzword (2025-05-12T11:41:00+05:30)

|

More than half of the world’s population currently lives in cities and this share is expected to rise to nearly 70% by 2050.

It’s no wonder “smart cities” have become a buzzword in urban planning, politics and tech circles, and even media. The phrase conjures images of self-driving buses, traffic lights controlled by artificial intelligence (AI) and buildings that manage their own energy use. But for all the attention the term receives, it’s not clear what actually makes a city smart. Is it about the number of sensors installed? The speed of the internet? The presence of a digital dashboard at the town hall? Governments regularly speak of future-ready cities and the promise of “digital transformation”. But when the term “smart city” is used in policy documents or on the campaign trail, it often lacks clarity. Over the past two decades, governments around the world have poured billions into smart city initiatives, often with more ambition than clarity. The result has been a patchwork of projects: some genuinely transformative, others flashy but shallow. So, what does it really mean for a city to be smart? And how can technology solve real urban problems, not just create new ones? What is a smart city, then?The term “smart city” has been applied to a wide range of urban technologies and initiatives – from traffic sensors and smart meters to autonomous vehicles and energy-efficient building systems. But a consistent, working definition remains elusive. In academic and policy circles, one widely accepted view is that a smart city is one where technology is used to enhance key urban outcomes: liveability, sustainability, social equity and, ultimately, people’s quality of life. What matters here is whether the application of technology leads to measurable improvements in the way people live, move and interact with the city around them. By that standard, many “smart city” initiatives fall short, not because the tools don’t exist, but because the focus is often on visibility and symbolic infrastructure rather than impact. This could be features like high-tech digital kiosks in public spaces that are visibly modern and offer some use and value, but do little to address core urban challenges. The reality of urban governance – messy, decentralised, often constrained – is a long way from the seamless dashboards and simulations often promised in promotional material. But there is a way to help join together the various aspects of city living, with the help of “digital twins”. Digital twin (of?) citiesMuch of the early focus on smart cities revolved around individual technologies: installing sensors, launching apps or creating control centres. But these tools often worked in isolation and offered limited insight into how the city functioned as a whole. City digital twins represent a shift in approach. Instead of layering technology onto existing systems, a city digital twin creates a virtual replica of those systems. It links real-time data across transport, energy, infrastructure and the environment. It’s a kind of living, evolving model of the city that changes as the real city changes. This enables planners and policymakers to test decisions before making them. They can simulate the impact of a new road, assess the risk of flooding in a changing climate or compare the outcomes of different zoning options. Used in this way, digital twins support decisions that are better informed, more responsive, and more in tune with how cities actually work. Not all digital twins operate at the same level. Some offer little more than 3D visualisations, while others bring in real-time data and support complex scenario testing. The most advanced ones don’t just simulate the city, but interact with it. Where it’s workingTo manage urban change, some cities are already using digital twins to support long-term planning and day-to-day decision-making – and not just as add-ons. In Singapore, the Virtual Singapore project is one of the most advanced city-scale digital twins in the world. It integrates high-resolution 3D models of Singapore with real-time and historical data from across the city. The platform has been used by government agencies to model energy consumption, assess climate and air flow impacts of new buildings, manage underground infrastructure, and explore zoning options based on risks like flooding in a highly constrained urban environment. In Helsinki, the Kalasatama digital twin has been used to evaluate solar energy potential, conduct wind simulations and plan building orientations. It has also been integrated into public engagement processes: the OpenCities Planner platform lets residents explore proposed developments and offer feedback before construction begins. We need a smarter conversation about smart citiesIf smart cities are going to matter, they must do more than sound and look good. They need to solve real problems, improve people’s lives and protect the privacy and integrity of the data they collect. That includes being built with strong safeguards against cyber threats. A connected city should not be a more vulnerable city. The term smart city has always been slippery – more aspiration than definition. That ambiguity makes it hard to measure whether, or how, a city becomes smart. But one thing is clear: being smart doesn’t mean flooding citizens with apps and screens, or wrapping public life in flashy tech. The smartest cities might not even feel digital on the surface. They would work quietly in the background, gather only the data they need, coordinate it well and use it to make citizens’ life safer, fairer and more efficient. Milad Haghani, Associate Professor & Principal Fellow in Urban Risk & Resilience, The University of Melbourne; Abbas Rajabifard, Professor in Geomatics and SDI, The University of Melbourne, and Benny Chen, Senior Research Fellow, Infrastructure Engineering, The University of Melbourne This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Digital mental health programs are inexpensive and innovative. But do they work? (2025-03-31T12:52:00+05:30)

|

Bonnie Clough, Griffith University; Aarthi Ganapathy, Edith Cowan University, and Lou Farrer, Australian National University Almost half of Australians will experience mental health problems in their lifetime. Recent floods, droughts, cyclones, bushfires and the COVID pandemic have increased distress in the community. Yet, many people who need mental health services are unable to access them. Cost, stigma and availability of mental health workers are barriers to care. Australia also has a critical shortage of mental health workers. And by 2030, it’s predicted we will be missing 42% of the mental health workforce needed to meet the demand. To partially address this gap, the Australian government has committed to investing A$135 million in digital mental health programs if re-elected. Online mental health programs can be more innovative and less expensive than other types of therapy. But do they actually work? Let’s assess the evidence. What are digital mental health services?Digital mental health services vary widely. They include online or app-based mental health information, symptom tracking tools, and learning or skills programs. These tools can be accessed with or without support from a therapist or coach, with some using generative generative artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning. The umbrella term “digital mental health services” also includes peer-support networks, phone helplines and human-delivered phone, chat, or video-based telehealth services. Services such as Mindspot, for example, offer online assessment, feedback and referrals to online treatments that have optional therapist support. Digital mental health services target a range of mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, trauma and eating disorders. Some are designed for specific groups of people, including culturally diverse communities, LGBTQIA+ people, new parents and young people. With so many digital options available, finding the right program can be challenging. The government-funded Medicare Mental Health portal was set up to help Australians find evidence-based services. Do they work?A 2020 review of the evidence found almost half of people who used online programs for common mental health conditions benefited. This review included online programs with self-directed lessons or modules to reduce symptoms of depression or anxiety. These programs were as effective as face-to-face therapy, but face-to-face therapy required on average 7.8 times more therapist time than online programs. The evidence for other types of digital mental health programs is still developing. The evidence for smartphone apps targeting mental health symptoms, for example, is mixed. While some studies have reported mental health benefits from the use of such apps, others have reported no differences in symptoms. Researchers suggest these apps should be used with other mental health supports rather than as standalone interventions. Similarly, while AI chatbots have received recent attention, there is uncertainty about the safety and effectiveness of these tools as a substitute for therapy. Chatbots, such as the AI “Woebot” for depression, can give users personalised guidance and support to learn therapeutic techniques. But while chatbots may have the potential to improve mental health, the results are largely inconclusive to date. There is also a lack of regulation in this field. Early studies also show some benefits for digital approaches in treating more complex mental health conditions, such as suicidal thoughts and behaviours, and psychosis. But more research is needed. Do users like them?Users have reported many benefits to digital mental health services. People find them convenient, accessible, private and affordable, and are often highly satisfied with them. Digital services are designed to directly address some of the major barriers to treatment access and have the potential to reach the significant numbers of people who go online for mental health information. Digital supports can also be used in a “stepped care” approach to treating mental health problems. This means people with less complex or less severe symptoms try a low-intensity digital program first before being “stepped up” to more intensive supports. The United Kingdom’s National Health Service’s Talking Therapies program uses this model.  The NHS Talking Therapies program includes the option of learning self-guided cognitive behaviour therapy techniques. NHS/Every Mind Matters (screenshot) The NHS Talking Therapies program includes the option of learning self-guided cognitive behaviour therapy techniques. NHS/Every Mind Matters (screenshot)But some people still prefer face-to-face services. Reasons for this include problems with internet connectivity, a perceived lack of treatment tailoring and personal connection, and concerns about quality of care. Some Australians face challenges with digital literacy and internet access, making it difficult to engage with online services. Privacy concerns may also discourage people from using digital platforms, as they worry about how their personal data is stored and shared. What do clinicians think about them?Mental health professionals increased their use of digital mental health tools (such as telehealth consultations) markedly during the COVID pandemic. Yet many clinicians struggle to use these tools because they have not received enough training or support. Even when willing, clinicians face workplace barriers which make it difficult to incorporate them into their practice. These include:

Some patients and clinicians prefer in-person therapy. VH-Studio/Shutterstock Some patients and clinicians prefer in-person therapy. VH-Studio/ShutterstockSome clinicians remain sceptical about whether digital services can truly match the quality of in-person therapy, leading to hesitation in recommending them to those who might benefit. What needs to happen next?With mental illness and suicide estimated to cost the Australian economy $70 billion per year, there are strong personal, social and financial reasons to support innovative solutions that increase access to mental health services. But for digital approaches to reach their full potential, we need to upskill the mental health workforce and support organisations to include digital technologies into their practice. It’s also important to improve awareness of digital mental health programs and reduce the barriers to accessing these services, or we risk leaving behind the very people who need them the most. For Australians with more complex mental health issues, or those for whom digital mental health treatment hasn’t worked, access to in-person therapy and other mental health treatments should remain available. Digital mental health programs are one part of the mental health care system, and not a replacement for all types of care. If you or anyone you know needs help or support, you can call Lifeline on 13 11 14. Bonnie Clough, Senior Lecturer, School of Applied Psychology, Griffith University; Aarthi Ganapathy, Senior Lecturer, Mental Health, Edith Cowan University, and Lou Farrer, Associate Professor and Registered Psychologist, Australian National University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

NZ is moving closer to digital IDs – it’s time to rethink how we protect our valuable data (2025-02-05T14:01:00+05:30)

|

New Zealand shifted closer towards digital credentials for access to online services this week with the launch of the Trust Framework Authority. It will determine which organisations are verified to provide digital identity services. The digital ID scheme aims to ease transactions such as opening a bank account or accessing government services by moving identity verification away from physical documents. This has the potential to transform New Zealand’s digital economy, and Minister for Digitising Government Judith Collins has already suggested she wants to expand the government’s use of AI, including in health and education. But both the launch of the authority and the push to expand AI are significant developments that need to be considered in the wider context of the principles on which our digital economy runs. While digital ID is key to access and trust in digital services, it needs to be protected and managed in accordance with our values, including personal, community and national perspectives. Digital ID is only one aspect of a wider digital economy. We have to consider more systemically how we develop new digital services and who develops them. Our new report, collaboratively produced by researchers from the Veracity Technology Spearhead project and the domestic cloud provider Catalyst Cloud, shows how digital ID is tightly interwoven with data management and information flow more generally. We highlight how the latest developments open a window of opportunity to fundamentally adjust how we build digital systems towards a decentralised model that disentangles data management from data processing. According to a recent OECD report, such an adjustment is urgently required to ensure citizens and businesses have choices and are safe in a digital world. Global developments in data infrastructureMany countries are recognising the importance of having their own national data infrastructures. In Estonia, the X-Road system has been a pioneer in this field. Launched in 2001, it is the foundation of the country’s e-government services, allowing secure data exchanges between public and private sector databases. This infrastructure has enabled Estonia to become a leader in digital government services, from online voting to digital health records. The European Union’s GAIA-X project aims to create a federated data infrastructure for Europe, promoting sovereign and interoperable data spaces. Recently, the EU launched a pilot phase of its digital identity wallet initiative, with uses ranging from banking to mobile driving licences and electronic prescriptions. The Flanders region in Belgium is the first in the world to establish a data utility provider to drive adoption of and innovation around so-called data vaults, using the Solid platform. This includes a service that allows citizens to take full control over data they accumulate throughout their professional careers, from qualifications to payroll data from various employers. Local businesses give away their dataWhile these global developments are promising, many local businesses find themselves in a difficult position. They rely on services provided by large tech companies for their digital operations, inadvertently handing over data in the process. Small retailers, for instance, may use e-commerce platforms that collect and analyse customer data. While these platforms provide valuable services, they also leak insights that can be used to compete with the very businesses they serve. A prominent example of the risk of uncontrolled data outflow is Samsung’s ban of the use of ChatGPT. Concerns arose that sensitive information would be leaked through the prompts employees used. This would become accessible to OpenAI and other users of ChatGPT by becoming part of the foundational language model that underpins it. Similarly, farmers using smart agriculture techniques may be sharing data about their crops, yields or soil quality with the service providers. This information becomes a valuable asset, but farmers cannot access or leverage it independently. The challenge for local businesses is clear. They need digital tools to remain competitive, but using these tools often means surrendering control over the data they collect. These data, in turn, fuel the growth and dominance of large tech companies, creating a cycle that’s difficult to break. Rebalancing the playing fieldAI startups should have more options for accessing a competitive foundation model than to adopt one that has been created by multinational companies under unclear conditions. This carries the risk of building technology that unknowingly imports components that may have been developed unethically, or which embed values that are incompatible with the local context. Norway has demonstrated leadership in this area. Its research centre for AI innovation, (NorwAI), develops and maintains a suite of Norwegian Large Language Models built on Norwegian data and values. NorwAI and the data utility company in Flanders are two examples of the potential for completely new organisational forms that generate value in a data infrastructure ecosystem. They exemplify that data infrastructures are key to rebalancing the digital economy for the benefit of everyone. They also show data infrastructures are not about creating walled gardens or preventing free flow of data when necessary. Instead, they provide protections so data flow happens only on agreed terms, and under full disclosure of what occurs once data have been transferred. The path to creating equitable national data infrastructures is complex and will require collaboration between governments, businesses and civil society. However, the potential benefits – increased innovation, fair competition and democratised access to the digital economy – make it a journey worth undertaking. Markus Luczak-Roesch, Professor of Informatics and Chair in Complexity Science, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Why we need to teach digital literacy in schools (2024-12-05T12:21:00+05:30)

|

In the modern world, screens are everywhere, from our classrooms and workplaces to our homes and pockets. For children and teenagers, they can be a window to learning, enjoyment and connection with the world. Too much screen time, however, can have serious consequences.

Adults spend, on average, between six and seven hours per day in front of screens. In Spain, like much of Europe, children and teenagers spend more than three hours per day looking at screens, though this figure can double at weekends. Such intense exposure has obvious problems, such as taking time from other beneficial activities like sport or socialising in person. It also has negative health impacts, ranging from from short-sightedness, headaches and musculoskeletal disorders to shorter attention spans and delays in the development of children’s problem solving and communication skills. Beyond the impacts of social media on young people’s mental health, the ubiquity of screens is prompting many families and teachers to wonder whether education without technology, or at least with less screen time, would be better. However, we also need to teach children how to deal with the internet and how to work with technology. Training young people in digital skills, such as critical thinking and cybersecurity, is essential to keeping them safe online. In addition, digital platforms such as Google Classroom, Duolingo and Kahoot! have revolutionised learning, making it both more convenient and more personalised in the classroom and at home. Balance is possibleSchools around the world are finding ways to balance the risks and benefits of technology in the classroom. One inspiring success story is that of a school in Finland that implemented a hybrid model combining digital learning with hands-on activities. As a result, students improved their academic performance and developed advanced technological skills. Other successful examples – such as the “Abraza tus valores” (Embrace your values) and “Párate a pensar” (Stop to think) programmes by Aldeas Infantiles SOS in Spain – promote the balanced use of technology among young people. The United States also boasts programmes such as that developed by The Step by Step School. This initiative emphasises the moderate and purposeful use of technology by incorporating educational apps that support children’s development and encourage creativity, setting clear limits for screen time, and promoting off-device activities such as outdoor play and hands-on projects. A question of equityScreens can provide access to knowledge and make our lives easier, but we cannot allow them to become a substitute for real human experiences. Digital education should be complemented by activities that develop social, emotional and physical skills. The solution to excessive screen use is not saying goodbye to technology in the classroom altogether. Ignoring these technological tools in education would deprive students of the skills they need to function in an increasingly interconnected world. Instead, we have to make sure they are used to their full potential. In Spain, 70% of children between the ages of 10 and 15 own a smartphone, with similar or higher figures reported across the EU. While these figures are high, they only give us half of the picture. Smartphones are tools, and like any tool, knowing how to use it properly and safely is vital. Children, like many adults, use the internet and social media uncritically. Being mere consumers of what the internet offers can seriously limit their capacity for social integration. This aspect of the digital divide is where schools can level the playing field by providing access to technological resources and promoting equity of opportunity. By implementing digital literacy programmes, they can ensure that all students, regardless of their socio-economic background, have an equal opportunity to succeed. This is a collective challenge, and parents, teachers and young people must all work together to build healthy, conscious habits. To do this, we have to answer crucial questions about how we use our time in front of screens, and how we can reap technology’s benefits without falling prey to its risks. At the end of the day, the goal is not to live without screens, but to learn to live with them in a smart way. Pedro Adalid Ruíz, Profesor Universitario de Políticas de Calidad Educativa y Planes de Mejora, Universidad CEU San Pablo This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

UK unveils US-style digital border permit (2024-10-14T14:07:00+05:30)

LONDON - The United Kingdom announced the rollout of an Electronic Travel Authorisation (ETA) scheme, with visitors from Qatar the first to use it from October. Qataris will apply in advance for an ETA, which authorises an individual to travel to the UK and which the government says will make border crossings more efficient and secure. By the end of 2024, ETAs will be required for all foreign visitors who are eligible to come visa-free for short stays, including from Europe. Currently, travellers from the continent and countries such as the United States and Australia do not need to make any form of application to visit to the UK. "Strengthening our border remains one of the government's top priorities," British Immigration Minister Robert Jenrick said. "ETAs will enhance our border security by increasing our knowledge about those seeking to come to the UK and preventing the arrival of those who pose a threat. "It will also improve travel for legitimate visitors, with those visiting from Gulf Cooperation Council states being among the first to benefit," he added. The United States has a similar scheme, the Electronic System for Travel Authorization (ESTA). As with the ESTA, the UK government said the application process would be online. Most visitors will apply via a mobile app and receive a "swift decision", it said. Once granted an ETA, individuals will be able to make multiple visits to the UK over a two-year period, but the government did not specify how much applications will cost. After the initial launch for Qatar, the scheme will be open to visitors from the rest of the Gulf Cooperation Council states and Jordan from February 2024. The European Union has plans to launch a similar electronic permit next year which, following Brexit, will include Britons.While Britain has left the EU, Ireland remains in the bloc. But Irish nationals will be exempt from the new UK scheme, as the two countries continue to share a "Common Travel Area". UK unveils US-style digital border permit |