|

Digital Innovation: On the Frontier of Financial and Digital Inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa (2024-04-08T12:24:00+05:30)

MasterCard By Mark Elliott, Division President of Mastercard, Sub-Saharan Africa: As the digital economy continues to grow, increasingly relevant financial solutions emerge. Consumers can access services that make their lives simpler, and businesses run more agile and efficient operations with enhanced potential. Governments can reach more citizens. Long-term prosperity comes into vision for more and more people. It is why financial inclusion is so critical. Because financial inclusion is the first step to financial security. At Mastercard, we are innovating for impact in financial and digital inclusion. In 2020, Mastercard doubled down on its financial inclusion commitment to connect a total of 1 billion individuals and 50 million micro and small merchants to the digital economy by 2025 – with a direct focus on 25 million women entrepreneurs. While this is a global goal, there is a vast amount of work to be done in Africa, because there's widespread inequality and exclusion that persists. We have a responsibility to continually think about how we can find different and more innovative ways to address this. Innovation unlocks digital inclusion: Local innovation is critical in driving inclusion. As a global technology company, we cannot simply pull things off the shelf from our product set in the US or Europe and expect it to work in Africa. This is especially true in an environment where many people may still have limited access to basic technology and financial services. To create products and services that truly solve the local pain points for communities in Africa, we must think carefully about the technology and partnerships that will further these goals. The adoption of digital payments is becoming increasingly relevant, and in Africa, mobile phone adoption is inextricably linked to this. For millions who have never had a brick-and-mortar bank account, leapfrogging legacy banking to digital first banking services is an easy transition. This dynamic makes it even more important for institutions in the financial payment space to adopt ‘Digital First’ platforms. The Mastercard Digital First program provides or partners with a complete digital experience in the world of payment methods. Digital First provides the customer with a 100% digital product: no paperwork, branch visits or snail mail. Customers can open a bank account immediately by uploading identification, apply for a card, activate it, and use it for all their payment needs from their mobile devices. A physical visit to a branch then becomes an optional extra. Though the financial sector is already digitally transforming, there are still some barriers to progress, which include a preference for cash – often in areas where there is limited infrastructure. It is important to note that access to the internet and data is a critical enabler for adoption of digital financial services. Digital inclusion is a prerequisite for financial inclusion. At Mastercard we are addressing this challenge through our partnership with Samsung, Airtel, and Asante Financial Services to put digital devices in the hands of more people who can pay for them with small, manageable instalments while also building a credit history. Digital commerce enabled for small businessesA stable, growing, connected small business can be the key to financial inclusion for the whole community. Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) have been trending toward digital banking and payments for some time and changed behaviours during the pandemic accelerated this shift. While small businesses traditionally lagged larger ones in omni-channel presence, the trend of shopping from home, and the need for touch-free payments in-store ignited a need for them to accept digital payments. Digital Innovation: On the Frontier of Financial and Digital Inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa |

Digital technologies have made the wonders of ancient manuscripts more accessible than ever, but there are risks and losses too (2024-03-06T13:33:00+05:30)

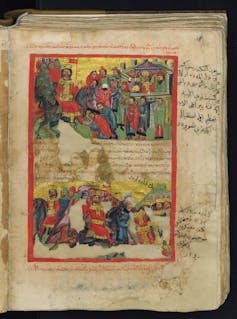

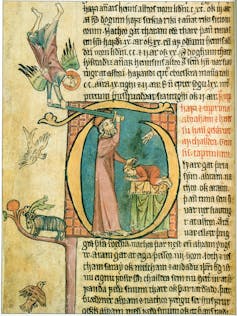

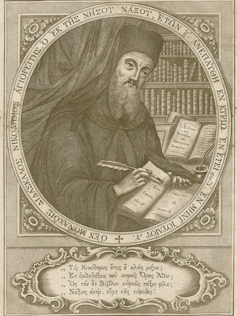

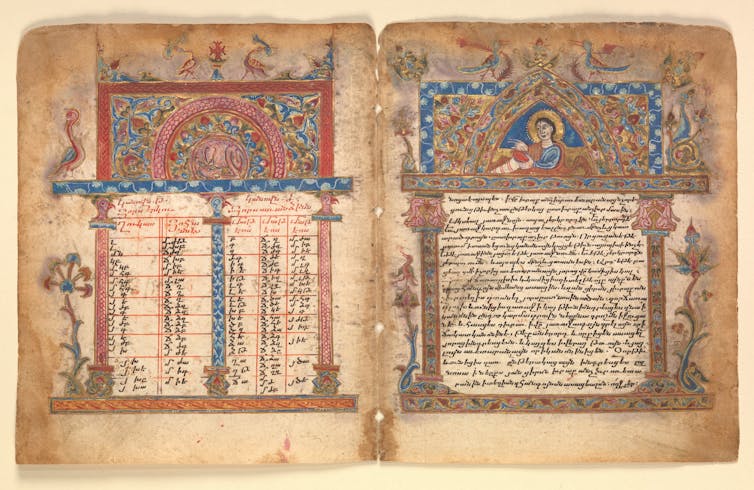

Detail from a 14th-century miniature Greek manuscript depicting scenes from the life of Alexander the Great. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Jonathan L. Zecher, Australian Catholic University Detail from a 14th-century miniature Greek manuscript depicting scenes from the life of Alexander the Great. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Jonathan L. Zecher, Australian Catholic UniversityNear the end of the 18th century, a Greek monk named Nikodemos was putting together a massive anthology of Byzantine texts on prayer and spirituality, which he would call The Philokalia. He lamented the state of learning among his fellow monks, because they did not have access to the texts of their tradition: Because of their great antiquity and their scarcity – not to mention the fact that they have never yet been printed – they have all but vanished. And even if some few have somehow survived, they are moth-eaten and in a state of decay, and remembered about as well as if they had never existed. Nikodemos hoped to correct this by collecting and printing texts that would otherwise fall to dust. By making the manuscripts into a book, he would preserve the knowledge they contained – but not the manuscript, not the artefact itself. He does not mention how difficult his Byzantine manuscripts were to read and transcribe, even for someone familiar with the language. Copying by hand takes dozens, even hundreds of hours of intensive labour. Reading them means learning to decode scribes’ handwriting, abbreviations and shorthand. Every manuscript, with its errors, notes and doodles – not to mention its artistry, images, and ornamentation – remains a unique artefact. The evanescent beauty of manuscripts is lost in their printed analogue. Every manuscript is its own text, its own space of knowledge, and an irreplaceable part of our shared cultural histories.  Nicodemos (1818). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Preserving the Past: Nikodemos was struggling with the perennial dilemma faced by historians and archivists. Our knowledge of the past, and the wisdom we can gain from it, is bound in material objects – whether manuscripts, paintings, ruined buildings or clay pots – that are decaying. Decay presents three challenges. What will we preserve of the past? How should we preserve it? And how do we ensure its accessibility? The scarcity and obscurity of ancient and medieval manuscripts are among the biggest obstacles to understanding both the texts they contain and the lives of those who wrote them. Few copies might ever have been made of a given text. We are lucky if we can now read a text in 50 manuscripts. Some survive in only one. But the biggest problems are time and the elements. Medieval manuscripts are usually made of parchment and bound in leather-covered boards. The ink is usually iron gall. These are amazingly durable materials, but they have their limits. Ink fades with exposure to light. Pages are torn or damaged by water, smoke and skin oils. The same activities that give us access to the manuscript will also slowly destroy it. Manuscript depicting scenes from the life of Alexander the Great, late Byzantine period (1204-1453). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons In the early modern period, antiquarians and collectors began acquiring manuscripts from monasteries and churches and putting them into libraries. Manuscript tourism became a popular activity for wealthy scholars like Sir Robert Cotton (1571-1631), whose collection became the core of the British Museum’s collection. Of course, many of these collectors simply stole or smuggled what they wanted from struggling monasteries in what are now Greece, Sinai and Israel. Their achievements must be balanced against their participation in colonial piracy. But their work made possible the rise of printed editions of classical and medieval works. The printing revolution promised a solution to preservation and accessibility. It accelerated distribution and made the task of reading easier by standardising printing conventions. Books could proliferate where manuscripts could not, and anyone who could read them could access that knowledge. But the printed version rarely resembles its parchment parent. Hand-copying always introduces errors, whether accidental or intentional, and so each manuscript copy differs from the next. Printed editions must choose one form. Usually, this means choosing between readings, combining them, or correcting as the editor deems best. Our modern editions of the Bible and the Iliad, for example, do not exactly match their underlying manuscripts. The texts represent editors’ best judgement of the originals.  Bear baiting, marginal illustration from a 14th century manuscript. British Library, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY Digital decay: Even if we prefer the edited versions, printed books decay faster than manuscripts, and take up just as much space. Print does not solve the problem of preservation; it only postpones it. In the 20th century, digital scanning tools and computer-based storage seemed to offer a new kind of solution. Manuscripts could be scanned into high-resolution images and stored digitally. Computers promised no more deterioration and no more shelf space. European and American libraries have invested millions in digitising their manuscript holdings. The Library of Congress, the British Library, and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, among others, offer access to thousands of manuscripts free of charge on their websites. The move online seems so perfect to some that the UK Ministry of Justice plans to digitise 100 million wills, and then destroy the paper originals.  Armenian manuscript, 15th century. Metropolitan Museum of Art, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY This proposed move ignores the inherent problems and vulnerabilities of digital solutions, which amount to “digital decay”. First, the digital image is not the same as the material original. Even the finest colour images do not let a reader change the lighting to bring out different colours, or look from different angles to see faded letters more clearly. You just can’t see as much in the scan as you can on the page. Second, digital images are often in proprietary formats, meaning that without the library’s viewing software you cannot actually examine the manuscript. Sometimes lower quality scans are available in formats like PDF and JPEG, but these are generally blurry, and even unreadable. In some cases, images cease to be accessible because they are contained in obsolete file formats. The digital format is still chained to its digital shelves in a private space. Third, as a recent cyber-attack on the British Library demonstrates, the digital space seems not to be safer than the physical one. On October 28, 2023, a criminal group called Rhysida unleashed ransomware in the British Library’s computer systems, stealing nearly 500,000 files. The most worrisome thefts were of personal information that could be used for identity theft and other frauds. But the British Library website has been down since that day. Its incident report page says that it may take up to a year to restore all online operations. That includes all of the library’s carefully digitised manuscripts, which are now unavailable. There is no sense of when we will see them again. The digital library space, with its proprietary viewing software and its specialised file formats, is now shuttered. Conservation and accessibility: Digitising manuscripts may promise preservation and accessibility, but it does not future-proof our access to the past. Scans and websites cannot make up for losing the real thing. Yet physical conservation comes at the expense of accessibility. We can, however, use advances in AI and computer technology to improve approaches to digital conservation and enable wider access to the uniqueness of individual manuscripts. To avoid digital decay, we need to devote the same attention to digital conservation as to material conservation. Long term investment is needed to regularly migrate file formats to keep up with changing technologies. Ideally, these formats should be “inter-operable” – which is to say, usable across a wide range of platforms. This would uncouple the digital objects from the proprietary viewers used by libraries now, so they can be stored and viewed anywhere, rather than only on library websites. Until that happens, each digital library space remains vulnerable to decay and even loss since, if the website is down, the viewer is down. Abraham’s sacrifice, 14th century manuscript. Árni Magnússon Institute. Szilas, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons It has become possible to train AI to “read” manuscripts, transcribe them, and assist in translating them into English, Chinese, Spanish, and so on. Images of manuscripts would then have a readable text and all the unique elements of the material original – its decorations and artistry, its errors and doodles. The underlying combination of inter-operable file formats and relatively simple software would mean museum visitors could use tablets and touch screens to read and interact with manuscripts, not just as artistic objects, but as readable texts. In this enhanced digital form, manuscripts could come to local museums, libraries and galleries, where they would be accessible to everyday visitors as well as specialists. This approach would require careful care for the material originals, as well as continuing investment in digital formats and technologies to ensure access for future readers. At the end of his introduction to the Philokalia, Nikodemos congratulates himself on what he offers readers: For behold, writings never ever published in earlier times! Behold, works which lay about in corners and holes and darkness, unknown and moth-eaten, and here and there cast aside and in a state of decay! The challenges of preserving and accessing our past, contained in objects like manuscripts, are not really that different from those Nikodemos faced in his day. But unlike him, we can now offer the experience of the manuscript as well as the text, and to a much wider audience.  Jonathan L. Zecher, Research fellow, Australian Catholic University, This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. Jonathan L. Zecher, Research fellow, Australian Catholic University, This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Ashok Ahuja: The Digital Traveller (2018-03-31T17:36:00+05:30)

Ashok Ahuja has not stopped discovering himself

By Georgina Maddox: DO NOT BE fooled by his grey locks and professorial appearance. Ashok Ahuja is a 65-year-old ‘geek’ who is as adept in the digital world as any 24-year- old youth who was born into the digital era. Whether it is a drawing or painting, photograph or an installation, Ahuja has translated space, light, memory and form into mysterious shapes and imagery for his solo exhibition ‘Allured’ that opened at Gallery Espace in Delhi. Ahuja may be seen as a man ahead of his time, for he bought his first computer in 1985, an era when many people in India were not even aware of words like ‘email’, ‘surf’ and ‘download’. His inquisitive mind has always been interested in the ‘allure’ of technology and he has extended his creative streak to many avenues and mediums. An author and a filmmaker, Ahuja is the kind of artist who is comfortable in several mediums of expression, without becoming a ‘Jack of all trades’. “I am grateful to work in more than one medium,” he says, “My mind is the first site where the creative idea germinates. Then the idea itself tells me whether it wants to be translated as a drawing, a photograph, a film or a book.” While it may seem like a redundant question in the age of Photoshop, one cannot help but wonder if Ahuja faced any criticism for working primarily in a digital medium, especially since he does not hail from a typical art-school background. “Does a poem become less of a literary work because it is written on a computer? I am guessing the answer is ‘no’. So why should it be different for art made on a computer? I look at the computer as a tool. The same way a painter would use a brush, paint or canvas, I use the camera, Photoshop or the inkjet printer. As long as the ideas take shape in my mind, how does it matter if I used paint or a printer?” asks the artist. Given that digital art has been around since the 1950s in the UK and other overseas countries, the debate around whether it is art or not may appear superfluous and dated. It is a concern that galleries, art critics and lay viewers have debated since the 2000s. Sean Frank and Margot Bowman (from 15 Folds, an online gallery that brings together GIF images by artists on the web) in a conversation at the British Council last year, discussed whether digital art is subjective. Bowman said, “The general public perception of art has definitely softened. Experiencing digital art is something that shouldn’t be intimidating because people have lots of other experiences digitally that they wouldn’t normally do in the real world.” Ahuja’s digitally produced art undoubtedly occupies the gallery in the same manner that a painting or sculpture would. Ahuja’s images are also an interesting coalescing of two worlds. Where his concerns are informed by over five decades of history and travel, his practice is informed by a digital era. His digitally produced images are not easy to decode. The viewer is required to spend time before the images reveal their meaning, whether it is the patterns formed by a repetition of familiar objects, like tiffin carriers, abstract line drawings, stick figures, or digitally montaged photographs of architectural spaces. Ahuja's digitally produced images are not straight forward. In fact, the viewer is required to spend time before the images reveal their meaning He has also done a series of self- portraits that bear a faint resemblance to American pop artist Andy Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe silk-screen prints. However, while Warhol talked about Monroe’s contrasting life in mass media through black-and-white and colour images, Ahuja’s self-portraits are a dialogue about race. The image is titled, tongue firmly in cheek, CMYK: Portrait of the artist as a Man of Color and consists of four images of the artist with his face coloured green, indigo, yellow and brown. The last figure is the portrait of the ‘artist’ as a Black person—a person of colour. It is significant that ‘CMYK’ stand for Cyan, Magenta, Yellow and Key (Black), which are the inks used in colour printing. “The work has to do with race, identity, and with discrimination. When you mix all the inks you get black! It refers to the origin of the human race—in Africa,” says Ahuja. The set of portraits is about the formation and fixing of identities, how we perceive them and react to them. “I believe a true artist is a sensitive person who empathises and identifies with those who are discriminated against,” he says, recalling that the work came out of two trips he made to Africa where he visited the International University of East Africa, Uganda, in 2010 and 2012. “Africa was a land of fertility and fecundity, its red soil, rushing waters, vast landscape and blue skies reminded me of our evolution. However, it provoked me to question my own unawareness about the world,” says Ahuja. “It made me question the self and the collective, society and its structures, like family, tribe, community and nation. It made me face unattractive truths about how racist people can be.” Questions also arose about politics and domination, about greed and the will to power, and the corruption of the human soul. “I wondered about the nature of hope, of peace, of faith and religion, and of the relationship between individual and collective destinies,” he adds, explaining further that CMYK: Portrait of the Artist as a Man of Color is only a small part of his process of a slow absorption of that rich and profound experience. Another set of works that catches one’s attention is a set of simple line drawings and stick figures. Titled Celestial Fables, they are inspired by the constellations. “The work is about universality, about ancient wisdom and understanding, about recognition and memory,” says Ahuja. These drawings speak about the magic of simplicity in a highly complex order. An installation titled Plan 1999 consists of seven framed units embedded within a single platform painted with cement to represent the structure of a building. They are laid out like an architectural plan of a dwelling, but they have many layers of detail and lived narratives. “Placing them horizontally brings out the idea of it being like an architectural ‘plan’. But once you enter, you realise that it is not just spatial but has other dimensions too,” says Ahuja. The collage-like nature of the work speaks of a fragmented memory, one that selectively recalls bits and pieces of one’s existence. His love for architecture grows from his fascination with how light creates shapes out of spaces. “For me, architecture is not just about bricks and mortar, it is about capturing the mood and the soul of the building, the way light falls on it and creates patterns and depth,” he says. Since the exhibition features works from different phases of Ahuja’s oeuvre, one is tempted to think of this as a retrospective. Ahuja, however, is quick to refute that notion. “I work all the time and often do not show my work, which is why I have decided to show works from over the last 12 years, but it is not by any standards a ‘retrospective’. I say this because I feel I have so much more work to give and to show,” he says. “Mostly it’s because my work is not ‘topical’. It tends to span time and can always be seen as relevant even after a long time.” (‘Allured’ is on till 15 October at Gallery Espace, New Delhi ) Source: OPEN Magazine

|

The Internet is losing its baby teeth (2016-03-18T01:26:00+05:30)

In 2010, Chris Anderson, editor of Wired magazine, wrote “The Web Is Dead.” He argued that the future of the Internet and connectivity wasn’t in the World Wide Web, but in a fragmented collection of many different platforms — people consuming content via mobile devices, native apps and other means outside of a traditional web browser. While Anderson’s sensational claim raised a lot of eyebrows, and sparked enormous debate, I wasn’t sure what to make of his prediction at the time. But four years later, we have a little more perspective. In 2014, ‘the web’ — the means by which we access the Internet using a web browser — is hardly dead, although there certainly has been a significant shift our relationship with the Internet. In its infant stages, going online meant using AOL or Earthlinkto dial up a connection to the web. Today, we use the Internet for different reasons, and our connectivity is better, faster and stronger than ever. The disruptive technology that is the Internet is no longer a baby, it’s more like a toddler learning to walk. When your babies learn to walk, you breathe a sigh of relief at their newfound mobility. But that relief quickly turns to frustration as you realize you’ve only traded one set of problems for another. Your newly mobile child can now get into everything, climb and break everything. The same is true with the Internet. One of the most astonishing ways it's changed our lives, for example, is by changing the way we consume music and videos. It’s severed our ties to old, “hard media” like videotapes, CDs and DVDs — an amazing liberation — but has also introduced a whole new, frustrating labyrinth of alternatives at the same time. Anderson’s prediction of fragmentation is most obvious when you look on top of (or under) your TV. Odds are, where we used to store our DVD cases and video sleeves, most of us now have an assortment of streaming devices. Instead of having one giant VCR, we can now choose from having a cable box, TiVO, DVR, Apple TV, Chromecast, Roku, Amazon Fire TV and much more. But the irony is that with all these choices, we can’t actually choose just one. You can’t stream iTunes media through your Chromecast, and you can’t watch Amazon Prime on your Apple TV. Roku is great, but doesn't work with AirPlay. You can watch Netflix on your Apple TV, but, of course, Netflix doesn’t have half the movies you wish it did available for streaming. If you want voice control on your device, only Amazon Fire TV has it. Are you the old fashioned type who still likes using a remote control? Don’t get Chromecast. Oh and by the way, if you don't want a wallet-sized device cluttering up your living room, you can just switch to Amazon’s new Fire TV Stick, which is about the size of a thumb drive. But that’s only if you don’t already have the Roku Streaming Stick, or if you aren’t waiting for Wal-Mart’s just-announced VUDU Spark Stick. (I can’t wait to see what Microsoft and Blackberry have up their sleeves to try to jump into this game — their product names are bound to be interesting.) I’m old enough to remember watching VHS tapes, but not enough to remember the video format wars in the ‘80s. My dad told me a story of the VHS tape fighting against the smaller, arguably better, Betamax format. As the story goes, VHS ended up with a better selection of videos – today we’d say they had more “content providers” — and ergo won the format war despite downfalls in size and picture quality. There was a similar war in the early 2000s: HD-DVD vs. Blu-Ray. But what this costly war actually proved was that hardware format doesn’t matter anymore. While people were busy upgrading their home video collections from VHS to HD-DVD or Blu-Ray, the Internet was born. Streaming digital media became the new way to watch movies and most of us stopped purchasing movies altogether, opting for monthly subscription fees for on-demand consumption using services like Netflix. The lure of the Internet delivering whatever we wanted, whenever and wherever we wanted and on any device wanted, trumped everything else. Is this all for the better? I still don’t know. I see benefit in no longer needing to spend my hard-earned cash on hardware that’ll become obsolete in five or 10 years, and not being confined to a desktop when I want to access web content. (I'm grateful to be free from lugging my massive CD sleeve around in my car too. However, there’s always the risk that I’ll want to listen to a certain album, or watch a certain movie, only to find out that it's “not available.”) I think we’ve reached an awkward phase for the Internet. It’s beyond the baby stages and learned to walk. It’s still gaining confidence, and smiles a big, toothy grin with several missing teeth. The web isn’t dead; we’re all just impatiently watching it to grow up. Ron is a web guy, IT guy, and Internet marketer living in Colorado Springs with his wife and five children. He can often be overheard saying things like "Get a Mac!" and "Data wins arguments,” wandering around the downtown area at least five days a week. Follow him on Twitter at@ronstauffer or email him at indy@ronstauffer.com. Questions, comments and snide remarks are always welcome. Source: Article, Image: https://flickr.com

|

Exploring history of digital revolution (2015-12-16T23:50:00+05:30)

The story of how the minds of those who created our current digital revolution like Lady Ada, Lovelace, Bill Gates, Steve Jobs and Larry Page worked and what made them so inventive is told in a new book by American writer and biographer Walter Isaacson. The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution is also a narrative of how the ability of these people to collaborate and master the art of teamwork made them even more creative. In his book, published by Simon & Schuster, Isaacson begins with Lovelace, Lord Byron’s daughter, who pioneered computer programming in the 1840s. He explores the fascinating personalities that created our current digital revolution, such as Vannevar Bush, Alan Turing, John von Neumann, J C R Licklider, Doug Engelbart, Robert Noyce, Gates, Steve Wozniak, Jobs, Tim Berners-Lee, and Page. Isaacson, who recently wrote the biography of Jobs, explores what were the talents that allowed certain inventors and entrepreneurs to turn their visionary ideas into disruptive realities, what led to their creative leaps and why some succeed and others fail. The author says the computer and the Internet are among the most important inventions of our era, but few people know who created them. “The tale of their teamwork is also important because we don’t often focus on how central that skill is to innovation. In this book I set out to report on how innovation actually happens in the real world... I focus on a dozen or so of the most significant breakthroughs of the digital age and the people who made them,” he says. Most of the successful innovators and entrepreneurs in the book had one thing in common: they were product people. “They were not primarily marketers or salesmen or financial types; when such folks took over companies, it was often to the detriment of sustained innovation,” Isaacson says. According to the author, just as combining the steam engine with ingenious machinery drove the Industrial Revolution, the combination of the computer and distributed networks led to a digital revolution that allowed anyone to create, disseminate, and access any information anywhere. He terms Ada’s contribution as both profound and inspirational. “More than Charles Babbage (regarded as father of computing) or any other person of her era, she was able to glimpse a future in which machines would become partners of the human imagination, together weaving tapestries as beautiful as those from Jacquard’s loom,” Isaacson says. Innovations, according to the author, often bear the imprint of the organisations that created them. “For the Internet, this was especially interesting, for it was built by a partnership among three groups: the military, universities and private corporation. What made the process even more fascinating was that this was not merely a loose-knot consortium with each group pursuing its own aims. “Instead, during and after World War II, the three groups had been fused together into an iron triangle: the military-industrial-academic complex,” the book says. The Internet was originally built to facilitate collaboration. By contrast, personal computers, especially those meant to be used at home, were devised as tools for individual creativity. For more than a decade, beginning in the early 1970s, the development of networks and that of home computers proceeded separately from one another. They finally began coming together in the late 1980s with the advent of modems, online services, and the Web. Isaacson began work on this book more than a decade ago. “It grew out of my fascination with the digital-age advances I had witnessed and also from my biography of Benjamin Franklin, who was an innovator, inventor, publisher, postal service pioneer, and all-around information networker and entrepreneur. I wanted to step away from doing biographies, which tend to emphasise the role of singular individuals... “My initial plan was to focus on the teams that invented the Internet. But when I interviewed Bill Gates, he convinced me that the simultaneous emergence of the Internet and the personal computer made for a richer tale. “I put this book on hold early in 2009, when I began working on a biography of Steve Jobs. But his story reinforced my interest in how the development of the Internet and computers intertwined, so as soon as I finished that book, I went back to work on this tale of digital-age innovators,” he says. Source: The Asian Age, Image: flickr.com

|

Children help parents on how to use Technology (2015-09-16T00:34:00+05:30)

Teresa Correa, University Diego Portales in Chile conducted a deep study, did a lot of surveys, conducted interviews, and found that youth helps parents learning in all technologies like computer, mobile, internet, social networking etc. It occurs up to 40% of the time. Children scores were higher compared to parents which shows that parents dont recognize the influence themselves. Parents also learned how to use technologies by self experimentation. This phenomenon mainly occurs with mothers and lower socioeconomic families. This is what happens among low income immigrant families where children plays a vital role in connecting between the family and the new environment. Digital media, recent innovations & new technologies attracts everyone in this universe, and this is a new environment for the children from poor families learning new things from school and friends. This spills over and in turn the children teach their parents. Past studies have connected younger family members influence of older family members with the computers and internet. "The fact that this bottom up technology transmission occurs more frequently among women and lower families has important implications" said Correa. "Women and poor people usually lag behind in the adoption and usage of technology. Many times, they do not have the means to acquire new technologies but, most importantly, they are less likely to have the knowledge, skills, perceived competence, and positive attitudes toward digital media. These results suggest that schools in lower income areas should be especially considered in government or foundation led intervention programs that promote usage of media."Source: Article

|

Digital vs. celluloid debate grips movie world (2015-09-15T08:50:00+05:30)

Director Quentin Tarantino lambasts digital film-making as nothing less than the "death of cinema as I know it". Converts hail it as a democratizing force for good that is cheaper and faster than celluloid.

A debate is raging in the film world about the merits of shooting movies on 35mm film versus digital cameras. In one corner are those who believe digital's practical and economic benefits make it impossible to resist, informs AFP. In the other, "purists" such as Tarantino and "The Dark Knight Rises" director Christopher Nolan who cherish the visual "texture" of 35mm and warn that something important is being lost. "The fact that most films now are not presented in 35mm means that the war is lost," Tarantino told the Cannes Film Festival last month, describing digital projections as "just television in public". "Apparently the whole world is OK with television in public - but what I knew as cinema is dead!" the "Pulp Fiction" and "Kill Bill" director said. JJ Abrams, another celluloid devotee, who has just started shooting the new "Star Wars" movie, has also warned that without 35mm "the standard for the highest, best quality" will be lost. Nolan, meanwhile, predicts that studios will allow 35mm to completely disappear unless directors insist on it. Alain Roulleau, whose family has run Paris's oldest cinema since 1948, however, dismisses all this as "nostalgia" - and points out that most studios have already stopped supplying films in 35mm. Located on the slopes of Montmartre, Paris's old artists' quarter, Studio 28 with its Jean Cocteau-designed lamps and painted red steps, has old-world charm in buckets. In the projection room, though, Roulleau has made sure this small independent cinema is bang up to date. Roulleau took the decision to install digital projection equipment four years ago and admits he "almost cried" when he saw the quality of the first digital images, which he described as "very icy, too perfect, with no atmosphere". Fortunately, he says, since then the quality has seen constant improvements and in the past year he has shown only two films in 35mm. "When you have a 35mm print, when the print is quite new the image is perfect, but after two weeks in a theatre you have little dark spots on the screen from the dust," he told AFP. "With digital, from the first screening to the last, six months later, it's the same quality of image," he said. Others stress that even movies shot in 35mm are now quickly converted to digital for distribution and that the real clincher is the impact on the studios' bottom line. Printing just one film on 35mm film and delivering it to the cinema where it will be shown can cost $1,500 alone - compared to $150 for digital. With a copy needed for each of several thousand cinemas, it is easy to see why digital seems to have won the day. Patrick DiRenna, founder of the New York-based Digital Film Academy, called the shift to digital a natural evolution, adding that the lower start-up costs were allowing new voices to be heard. "The cameras are now almost completely there. The only thing that's lacking at this point is a slight level of picture quality, but that will change and in exchange we have democratization with artists who are now really able to do their work," he said. Shooting a film on a digital camera, he said, was like "sculpting in clay not marble" with directors able to keep reshaping until "you get to where you need to go". And he predicted that Tarantino too would eventually be won round. "Great artists like Quentin Tarantino are generally uncomfortable when they come across something new," DiRenna said. "Charlie Chaplin's discomfort with talkies is a perfect example - but when he finally made the adjustment, he turned around and made the 'The Great Dictator' and his mastery showed through again," he said. For now, however, Tarantino shows no sign of wavering. In Cannes, he added that he viewed the current generation of film-makers as a lost cause and lived in hope that 35mm could make a comeback. "I'm hopeful that we're going through a woozy, romantic period with the ease of digital," he said. "While this generation is completely hopeless, (I hope) that the next generation that will come up will demand the real thing -- in the way that after 20 years, albums are slowly coming back." Source: Voice Of Russia, Reference-Image: https://upload.wikimedia.org

|

In our digital world, are young people losing the ability to read emotions? (2015-04-28T21:47:00+05:30)

Children's social skills may be declining as they have less time for face-to-face interaction due to their increased use of digital media, according to a psychological study by the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

UCLA scientists found that sixth-graders who went five days without even glancing at a smartphone, television or other digital screen did substantially better at reading human emotions than sixth-graders from the same school who continued to spend hours each day looking at their electronic devices. “Many people are looking at the benefits of digital media in education, and not many are looking at the costs,” said Patricia Greenfield, a distinguished professor of psychology at UCLA College and senior author of the study. “Decreased sensitivity to emotional cues — losing the ability to understand the emotions of other people — is one of the costs. The displacement of in-person social interaction by screen interaction seems to be reducing social skills.” Researchers studied two sets of sixth-graders from a Southern California public school: 51 who lived together for five days at the Pali Institute, a nature and science camp about 70 miles east of Los Angeles, and 54 others from the same school. The camp doesn’t allow students to use electronic devices — a policy that many students found to be challenging for the first couple of days. Most adapted quickly, however, according to camp counsellors. At the beginning and end of the study, both groups were evaluated on their ability to recognise people’s emotions in photos and videos. The students were shown 48 pictures of faces that were happy, sad, angry or scared, and asked to identify their feelings. They also watched videos of actors interacting with one another and were instructed to describe the characters’ emotions. In one scene, students take a test and submit it to a teacher; one of the students is confident and excited, the other is anxious. In another scene, one student is saddened after being excluded from a conversation. The children who had been at the nature camp improved significantly over the five days in their ability to read facial emotions and other non-verbal cues to emotion, compared with the students who continued to use their media devices. Researchers tracked how many errors the students made when attempting to identify the emotions in the photos and videos. When analysing photos, for example, those at the camp made an average of 9.41 errors at the end of the study, down from 14.02 at the beginning. The students who didn’t attend the camp recorded a significantly smaller change. For the videos, the students who went to camp improved significantly, while the scores of the students who did not attend camp showed no change. The findings applied equally to both boys and girls. “You can’t learn non-verbal emotional cues from a screen in the way you can learn it from face-to-face communication,” said Yalda Uhls, lead author and senior researcher with the UCLA’s Children’s Digital Media Center, Los Angeles. “If you’re not practicing face-to-face communication, you could be losing important social skills.” Students participating in the study reported that they text, watch television and play video games for an average of four-and-a-half hours on a typical school day. Some surveys have found that the figure is even higher nationally. Greenfield considers the results significant, given that they occurred after only five days. The implications of the research are that people need more face-to-face interaction — and that even when people use digital media for social interaction, they’re spending less time developing social skills and learning to read non-verbal cues. “We’ve shown a model of what more face-to-face interaction can do,” Greenfield said. “Social interaction is needed to develop skills in understanding the emotions of other people.” Emoticons are a poor substitute for face-to-face communication, Uhls concluded: “We are social creatures. We need device-free time.” The research will appear in the October print edition of Computers in Human Behavior and is already. published online, Source: futuretimeline.net

|

Online News ‘Takes Off In US And UK While Most Germans Prefer A Newspaper’ (2015-04-19T16:30:00+05:30)

Example of newspaper front page : Credit: Wikipedia

The University of Oxford has launched a major study to examine how the digital revolution is changing the way we access news. Among the first findings published today, it shows that of those surveyed, most Germans still prefer a newspaper. Meanwhile, online news has overtaken print and TV news as the most frequently used medium in the UK and US for those using computers, mobile phones and tablets for news. One in five people in the UK now shares news stories every week through social networks or e-mail. However, the report also suggests out of the five countries studied, consumers in the UK were the most resistant to the idea of paying for online news. The Reuters Institute Digital News Report, published by the University’s Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, is based on the findings of YouGov surveys in UK, US, France, Germany and Denmark. The report finds that more than a quarter (28%) of those surveyed in the US and UK access news via their mobile each week. Six out of ten tablet owners in the UK said they regularly accessed online news. In the UK, mobile phone users are more concerned about the cost of accessing news (32%) than those who accessed news on a computer. Of tablet users (generally from a higher-income bracket), 58% use the device to access news every week and are more likely to pay for news content. Some newspaper brands with paid apps did significantly better on a tablet than on the open internet. Four out of ten tablet users say accessing news on the device is a better experience than on a personal computer. Overall, in the UK only four per cent of those surveyed said they had paid for online news, while Denmark had the highest percentage (12%) of consumers, of the countries studied, who have paid for online news. Report author Nic Newman, a Research Associate at Oxford University’s Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, said: ‘For many people digital news is now the first place to go for the latest news, rivalling television as the most frequently accessed type of news in the UK and the US. Of those surveyed, nearly eight out of ten people accessed online news every week, but the transition from print to digital is much slower in other European countries. The report suggests that the Germans were the least likely to access news online of the five countries studied with almost seven out of ten, of those surveyed, saying they still read a newspaper.’ The report also shows that in the UK, celebrity news is perceived to be more important – and news about politics less important – compared to the other countries surveyed. There is more interest in business and economic news in the UK and the US than in the European countries surveyed. The young also watch fewer traditional television news bulletins than older people. The young listen to far less news on radio, but spend far more time accessing news on their mobiles than older people. They are also more likely to use social media rather than search for news, whereas for older groups it is the other way round. In general, Europe lags behind the US in both the sharing of news and other forms of digital participation. In the UK, Facebook is the most important network for news, accounting for over half (55%) of all news sharing, followed by email (33%) and Twitter (23%). The Reuters Institute Digital News Report is the first in a series of reports that the RISJ hopes to publish over the coming years, tracking the changes in the public’s use of digital and traditional media to access news. The online surveys were conducted for Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism by YouGov in April 2012. The report reflects only the views of online users and excludes respondents who expressed no interest in accessing news at all. Contacts and sources: Oxford University, Note: The full report will be available on the RISJ website at on 9 July 2012. . It contains graphics and diagrams to illustrate the findings. YouGov conducted online surveys with representative samples from five countries: In UK, a total of 2,487 people (including 314 tablet owners); in US, a total of 814; in France, a total of 1,011; in Germany, a total of 970; and in Denmark, a total of 1,002. All the surveys were conducted in April 2012. The research for the Reuters Institute Digital News Report was supported by YouGov, Ofcom, BBC and the City University, London. The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) is University of Oxford’s centre for research into news media. The Thomson Reuters Foundation is the core funder of the RISJ, based in the Department of Politics and International Relations. The Institute was launched in November 2006 and developed from the Reuters Fellowship Programme, established at Oxford 29 years ago. The Institute, an international research centre in the comparative study of journalism, aims to be global in its perspective and provides a leading forum for scholars from a wide range of disciplines to engage with journalists from around the world. http://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/. Source: ineffableisland.com, Reference-Image: wikimedia

|

Russians more ambiguous about digital privacy (2015-04-15T09:30:00+05:30)

The NSA scandal which erupted last year has motivated governments to rethink their approach to internet and legislation, at least when it comes to protecting personal information. Let’s take a look at Russia, though. According to a poll conducted by EMC, 92% of Russians support legislation banning companies from processing and sharing information without users agreeing. Listen on air and read more on our daily Runet review '.RU' at the voiceofrussia.com.

Internet is a relatively young phenomenon – an extremely young if we look at the big picture, i.e. the history of humanity. However, it has stormed the world, destroying old paradigms and creating new ones, and the resulting mess cannot be truly comprehended using traditional methods. For example, take national legislation – how exactly should it work? It was pretty much black and white in pre-internet days. You do something on the territory of a country, you follow the laws of this county. But internet blurs national boundaries, with users, routing points, servers and other users scattered across the globe. But that’s, of course, just part of the problems traditional legislation has with the difficult to describe information-based medium. The NSA scandal which erupted last year has motivated governments to rethink their approach to internet and legislation, at least when it comes to protecting personal information. But perhaps it would best to use an international approach? This spring, on the 25 year anniversary of writing the first draft for the first proposal of the world wide web, its author, Sir Tim Berners-Lee, proposed creation of the online Magna Carta – a charter which would protect and safeguard the independence of the digital medium, along with rights of its users to freedom of expression and privacy worldwide. The proposal did not come out of the blue – talks on introducing legal guarantees for internet and its users have been voiced for a while now; proponents of legally established internet freedoms have become increasingly vocal, as I’ve said, after revelations leaked by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden. Essentially this project is a crowdsourcing effort for all internet users to create a digital bill of rights in each respective country. Berners-Lee said he hoped the intiative would be supported by public institutions, government officials and corporations. Ufortunately, nothing came of it yet. The possible reason for inaction is people simply don’t care much about their online freedoms and privacy – until they’re directly affected, of course.: Here’s an example: in 2012 Facebook tried holding a vote for new user policies, but it failed miserably. The seemingly ever-increasing general dissatisfaction concerning their privacy policy prompted Facebook to announce a massive network-wide vote on privacy. Well, a lot of people simply didn’t know there was a vote going on or didn’t care. The social network stated that 30% turnout was needed in order for the management to adhere to the people’s choice. Well, the final figures are nowhere near. Out of 900 million users the social network had at the time, a mere 342,632 voted on which privacy policy would govern the site. That’s less than 1% of the Facebook userbase. Let’s take a look at Russia, though. According to a poll conducted by EMC, 38% of Russians are ready to provide personal information for better online services. According to EMC Privacy Index, approximately one in four people worldwide care about privacy and are willing to provide information, with Germans being the most proactive – only 12% are ready to share personal data. Maybe it has something to do with experience. 61% of Russian users had to deal with violation of privacy in the past. In fact, 92% of Russians support legislation banning companies from processing and sharing information without users agreeing. Peter Lekarev, Source: The Voice of Russia, Image: pixabay.com under Creative Commons CC0

|

Hardening Against Disaster by Going Digital (2015-04-07T11:12:00+05:30)

When tropical storm Irene decimated parts of Vermont, a state program stepped in to ramp up digital development in response. “Never let a crisis go wasted,” says the program’s director.

By Dale Mackey When tropical storm Irene wiped out a month’s worth of timber sales, Vermont logger Carl Russell, who lives off the grid, responded by going digital. Russell is a sustainable logger and forestry consultant in Bethel, Vermont. In August 2011, Irene washed away approximately 25,000 board feet of timber he had hauled from the woods and stacked by the road. Russell contacted the Vermont Digital Economy Project, which helped him acquire an iPad and use it to collect data, manage his logging plan, present information to clients and connect with other loggers. “A lot of people draw this odd look because here I am a horse logger, and I built my house by hand,” Russell said. “I live off-grid. … But I’ve never really been afraid of digital technology. I see it as another tool in my toolbox. I’m still out in the woods with horses rolling logs by hand, but I have my iPhone and my iPad with me.” Russell wasn’t alone in having to reassemble the pieces after Irene struck. Throughout Vermont, small towns were devastated. While the state began disaster relief, the Vermont Council on Rural Development began its own approach to community recovery. The council established the Vermont Digital Economy Project, which used the immediate need for disaster relief as a way to help communities get ready for future disruptions. They created and shared digital tools with town governments, non-profits and small business owners. Another participant in the Digital Economy Project was Bridport Creamery, founded in 2012 by cheese-makers Nicky Foster and Julie Danyew. While Foster and Danyew knew a lot about making cheese, they needed help with their digital marketing. The digital project paired them with an adviser to help develop their online store. “We’ve had a lot of visitors who never would have known about us because they found us online,” Foster said, “It’s definitely benefitted us.” Strengthening local institutions through digital tools helps communities recover more quickly when difficulties like storms and natural disasters arise, says Paul Costello, executive director of the Digital Economy Project. “We take the whole idea of resiliency and emergency preparedness and say, yes these things are great for emergencies and that’s very important,” he said. “But let’s do it for every day. Let’s enrich the culture, enrich the community and enrich the business opportunities. All of those things make us stronger as communities and better prepared for future challenges. ” Starting in 2012, over the course of 18 months, the digital project has set out to make access to broadband ubiquitous in Vermont’s small towns. They expanded and established local social networks. They worked with libraries to provide digital literacy staff. They also recognized the need help the state’s innovation economy. “Vermont has always been a really creative place,” Costello said. “For such a small state of 625,000 people, we’re always at the top of the list for per-capita patent development.” Vermont doesn’t have a large manufacturing base, so small businesses are even more vital to Vermont’s economy and quality of life, says Costello. The natural disaster put that into sharp focus. “So many of these rural businesses are so fragile that anything we could do to strengthen their operation and reach and marketing, we wanted to do that, too,” Costello said. The Digital Economy Project offered a range of services, including free website development, record keeping management, marketing help and “social media surgeries” that helped build social media presence. The project provided one-on-one sessions with 266 businesses to make sure they understood how to use these tools effectively. Offering these services isn’t charity but an investment in Vermont’s small towns and communities, Costello said. It’s a model that could work for other places in rural America, he said. “We have to say that rural America is going to be the bread basket and the energy center for this country, but it’s also going to be a creative center for small business development across the board,” Costello said. “And we’re going to do that by using the most cutting-edge rural digital tools and having an enviable life as communities.” Costello said the 2011 tropical storm provided the inspiration to implement ideas that state had been talking about for years. “Never let a crisis go wasted,” he said. Source: http://www.dailyyonder.com/. .......................

Photo by LIsa McCroryCarl Russell and his logging "machine."

Nicky Foster and Julie Danyew of the Bridport Creamery.

|