Wei Zhai, University of Texas at ArlingtonWhen city leaders talk about making a town “smart,” they’re usually talking about urban digital twins. These are essentially high-tech, 3D computer models of cities. They are filled with data about buildings, roads and utilities. Built using precision tools like cameras and LiDAR – light detection and ranging – scanners, these twins are great at showing what a city looks like physically. But in their rush to map the concrete, researchers, software developers and city planners have missed the most dynamic part of urban life: people. People move, live and interact inside those buildings and on those streets. This omission creates a serious problem. While an urban digital twin may perfectly replicate the buildings and infrastructure, it often ignores how people use the parks, walk on the sidewalks, or find their way to the bus. This is an incomplete picture; it cannot truly help solve complex urban challenges or guide fair development. To overcome this problem, digital twins will need to widen their focus beyond physical objects and incorporate realistic human behaviors. Though there is ample data about a city’s inhabitants, using it poses a significant privacy risk. I’m a public affairs and planning scholar. My colleagues and I believe the solution to producing more complete urban digital twins is to use synthetic data that closely approximates real people’s data.“ The privacy barrierTo build a humane, inclusive digital twin, it’s critical to include detailed data on how people behave. And the model should represent the diversity of a city’s population, including families with young children, disabled residents and retirees. Unfortunately, relying solely on real-world data is impractical and ethically challenging. The primary obstacles are significant, starting with strict privacy laws. Rules such as the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR, often prevent researchers and others from widely sharing sensitive personal information. This wall of privacy stops researchers from easily comparing results and limits our ability to learn from past studies. Furthermore, real-world data is often unfair. Data collection tends to be uneven, missing large groups of people. Training a computer model using data where low-income neighborhoods have sparse sensor coverage means the model will simply repeat and even magnify that original unfairness. To compensate for this, researchers can use the statistical technique of weighting the data in the models to make up for the underrepresentation. Synthetic data offers a practical solution. It is artificial information generated by computers that mimics the statistical patterns of real-world data. This protects privacy while filling critical data gaps. Synthetic data: Tool for fairer citiesAdding synthetic human dynamics fundamentally changes digital twins. It shifts them from static models of infrastructure to dynamic simulations that show how people live in the city. By generating synthetic patterns of walking, bus riding and public space use, planners can include a wider, more inclusive range of human actions in the models. For example, Bogotá, Colombia, is using a digital twin to model its TransMilenio bus rapid transit system. Instead of relying only on limited or privacy-sensitive real-world sensor data, the city planners generated synthetic data to fill the digital twin. Such data artificially creates millions of simulated bus arrivals, vehicle speeds and queue lengths, all based on the statistical patterns – peak times, off-peak times – of actual TransMilenio operations. This approach transforms urban planning in several crucial ways, making simulations more realistic and diverse. For example, planners can use synthetic pedestrian data to model how elderly and disabled residents would navigate a new urban design. It also allows for risk-free testing of ideas. Planners can simulate diverse synthetic populations to see how a new flood evacuation plan would affect various groups, all without risking anyone’s safety or privacy in the real world. Making digital twins trustworthyFor all the promises of synthetic data, it can only be helpful if planners can trust it. Since they base major decisions on these virtual worlds, the synthetic data must be proved to be a reliable replacement for real-world data. Planners can test this by checking to see if the main policy decisions they reach using the synthetic data are the same ones they would have made using real-world data that puts people’s privacy at risk. If the decisions match, the synthetic data is trustworthy enough to use for that planning task going forward. Beyond technical checks, it’s important to consider fairness. This means routinely auditing the synthetic models to check for any hidden biases or underrepresentation across different groups. For example, planners can make sure an emergency evacuation plan in the urban digital twin works for elderly residents with mobility issues. Most importantly, I believe planners should include their communities. Establishing citizen advisory boards and designing the synthetic data and simulation scenarios directly with the people who live in the city helps ensure that their experiences are accurately reflected. By moving beyond static infrastructure to dynamic environments that include people’s behavior, synthetic data is set to play a critical role in urban planning. It will shape the resilient, inclusive and human-centered urban digital twins of the future. Wei Zhai, Associate Professor of Public Affairs and Planning, University of Texas at Arlington This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Spending too much time online? Try these helpful tips to improve your digital wellness (2025-12-22T13:10:00+05:30)

Bindiya Dutt, University of Stavanger and Mary Lynn Young, University of British Columbia Using digital platforms is increasingly the only option to manage our daily lives, from filling out forms at the doctor’s office or government offices to ordering food, booking a cab, paying taxes, banking, shopping or dating. Often, people are coerced into using apps or online platforms by the absence of any other options.Our social lives are equally entrenched in social media platforms. While the availability of services and opportunities on digital platforms may offer easier access or create an impression of wider connections, it also potentially harms our wellbeing. The adverse impacts of digital use have grown since the pandemic, as social isolation has increased dependence on these technologies. Impacts of excessive use of digital technologies range from physical problems such as increasing eye strain or dry eye to emotional concerns such as social media dependence. This in turn could trigger mental health issues due to online comparison and trolling. Other effects of platform dependence involve data privacy concerns with artificial intelligence and digital fraud. Likewise, social media comes with peer pressure, including the fear of missing out or social ostracism for not following digital trends. These affect our physical, mental, emotional and financial wellbeing. Recognizing and managing digital problems can improve our digital wellbeing. For some, digital autonomy refers to being in charge of personal data or having the right to withdraw consent from digital platforms. For others, it may be the ability to turn away from digital use and access non-digital options. Digital independenceChoosing to reduce or eliminate the use of digital platforms might seem like a feasible option. However, the coercive nature of these systems limits the availability of non-digital alternatives. For example, Meta’s refusal to share Canadian news media content had real impacts, highlighting people’s dependence on platforms for important news. The question of our autonomy as digital users is complex, as seen in the current conversation around smartphone use and its potential ban in classrooms. This touches on issues such as the relationship between self-regulation and government regulation. Another example emerges in the choices of how schools integrate digital learning — access versus screen time for example. Schools sometimes provide devices to students, and although this bridges the digital divide, it raises the question of whether students should be constantly available on digital devices? What alternatives can there be to digital platforms? How can we create an environment with varied choices while providing non-digital alternatives to accommodate individuals prone to digital addiction? Conversely, how might individuals averse to digital platforms or those lacking digital accessibility avail non-digital opportunities? Wellbeing comprises of creating a pleasant flow in all areas of life including physical, mental, emotional, financial and spiritual. Digital risks and digital overload can have detrimental effects on different areas of life including interpersonal relationships, productivity, sleep patterns and the quality of life. Wellbeing in the digital space largely depends on how we navigate the challenges and opportunities presented by technology. This could mean taking actions like monitoring screen-time, refraining from random scrolling, partaking in offline activities and understanding the risks of digital overuse. Focusing on balanced and ethical use of technology while addressing the potential negative consequences can help deflect negative impacts. Yet there are larger roles and responsibilities for platform creators and government bodies to protect us from digital dependence, such as offering non-digital options. While we do not yet have complete agency over our data privacy, we can gain agency over our digital usage by encouraging opportunities for non-digital alternatives. Tools for digital wellbeingTo manage digital dependence and overload, service providers can offer non-digital options. Engaging with technology without becoming dependent on it can contribute to physical, psychological, social and financial wellbeing. Incorporating some daily practices, creating new digital habits, and striking a healthy balance between digital use and non-use can support wellbeing. Tracking Paying attention to our daily digital usage and monitoring screen time helps us understand how, why and when we get drawn to our devices. Using the devices purposefully may assist in finding alternative activities. Taking screen breaks Turning off notifications or completely switching off for some time each day encourages us to take notice of the surroundings. Creating a digital curfew Setting up a specific cut-off time for digital devices some hours before bedtime can improve sleep hygiene. Tech-free days Assigning a day in a week or month which is tech-free helps to unplug digitally, limit digital dependence and help regain a sense of autonomy. Assigning a specific space for devices Allotting a space for all devices helps to keep them away from certain areas of the home which are meant for rest. Forming offline social connections Staying away from digital devices while meeting friends in person can curb digital usage and bolster social connections. Being wary of digital red flags

Learning how to identify a scam and validating websites before making online payments helps to avoid financial scams. Similarly, exercising due diligence when navigating online sites and social media platforms can help avert falling prey to cat-fishing which can lead to both emotional and financial losses. Bindiya Dutt, Doctoral Candidate, Media and Communication, University of Stavanger and Mary Lynn Young, Professor, School of Journalism, Writing and Media, University of British Columbia This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

‘Digital doppelgangers’ are helping scientists tackle everyday problems – and showing what makes us human (2025-12-17T11:23:00+05:30)

Alicia (Lucy) Cameron, CSIRO and Sarah Vivienne Bentley, CSIROAs rising seas lap at its shore, Tuvalu faces an existential threat. In an effort to preserve the tiny island nation in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, its government has been building a “digital twin” of the entire country. Digital twins are exactly what they sound like – a virtual double or replica of a physical, real-world entity. Scientists have been creating digital twins of everything from molecules, to infrastructure, and even entire planets. It’s also now possible to construct a digital twin of an individual person. In other words, a “digital doppelganger”. A doppelganger is someone who looks spookily like you but isn’t. The word originated in German, and literally means a “double walker”. A number of industries are now using digital doppelgangers for a range of reasons. These include enhancing athletic performance, offering more personalised healthcare and improving workplace safety. But although there are benefits to this technology, there are significant risks associated with its development. Having digital doppelgangers also forces us to reflect on which of our human attributes can’t be digitally replicated. Modelling complex systemsThe development of digital twins has been enabled by advances in environmental sensors, camera vision, augmented reality and virtual reality, as well as machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI). A digital twin allows us to build and test things in cyberspace – cheaply and without risk – before deploying in the real world. For example, we can build and stress-test infrastructure such as bridges or water supply pipes under a variety of conditions. Once built, we can use digital models to maintain the infrastructure proactively and prevent disastrous and costly structural breakdowns. This technology is a game-changer for planning and engineering, not only saving billions of dollars, but also supporting sustainability efforts. Of course, replicating individual humans requires much more complex modelling than when building digital twins of bridges or buildings. For a start, humans don’t live in a structured world, but rather inhabit complex social and physical environments. We are variable, moody and motivated by any number of factors, from hunger to tiredness, love to anger. We can change our past patterns with conscious thought, as well as act spontaneously and with creativity, challenging the status quo if needed. Because of this, creating perfect digital twins of humans is incredibly challenging – if not impossible. Nevertheless, digital doppelgangers are still useful for a number of purposes. The digital patientClinicians increasingly use scans to create virtual models of the human body, with which to plan operations or create artificial body parts. By adding extra biometric information (for example, blood chemistry, biomechanics and physiological responses), digital models can also mirror real-world bodies, live and in real time. Creating digital patients can optimise treatment responses in a move away from one-size-treats-all healthcare. This means drugs, dosages and rehabilitation plans can be personalised, as well as being thoroughly tested before being applied to real people. Digital patients can also increase the accessibility of medical expertise to people living in remote locations. And what’s more, using multiple digital humans means some clinical trials can now be performed virtually. Scaled up further, this technology allows for societal-level simulations with which to better manage public health events, such as air pollution, pandemics or tsunamis. The digital athleteImagine being able to train against a digital replica of an upcoming opponent. Sports scientists are increasingly working with digital athletes to trial and optimise strength and conditioning regimes, as well as test competitive play. This helps to increase the chances of winning as well as prevent injuries. Researchers at Griffith University have been pioneers in this space, creating models of real athletes. They have also trialled wearable sensors in patches or smart clothing that can measure a range of biomarkers: blood pressure and chemistry, temperature, and sweat composition. CSIRO and the Australian Sports Commission have also used digital humans to improve the performance of divers, swimmers and rowers. The digital workerAs well as building virtual replicas of sports people, scientists at CSIRO have also being building virtual simulations of employees in various workplaces, including offices and construction sites. This is helping them analyse movements, workflows and productivity – with the broader aim of preventing workplace injuries. For example, scientists can use a model of a digital worker to assess how heavy items are lifted in order to better understand how this puts strain on different parts of the body. With 6.1 million Australians impacted by musculoskeletal conditions, preventing workplace injuries can not only improve lives, but save the economy billions of dollars. Building a digital doppelgangers requires a lot of very personal data. This can include scans, voice and video recordings, or performance and health data. Personal data can also be harvested from an array of other sources. These include as cars, mobile phones, and internet-connected smart devices. The creation of data-hungry digital replicas is forcing us to redefine legal rights. Think copyright, deepfakes and identity theft or online scams. The power of this technology is inspiring. But ensuring a future in which we live happily alongside our digital doppelgangers will require governments, technology developers and end-users to think hard about issues of consent, ethical data management and the potential for misuse of this technology. Alicia (Lucy) Cameron, Principal Research Consultant & Team Leader, Data61, CSIRO and Sarah Vivienne Bentley, Research Scientist, Responsible Innovation, Data61, CSIRO This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

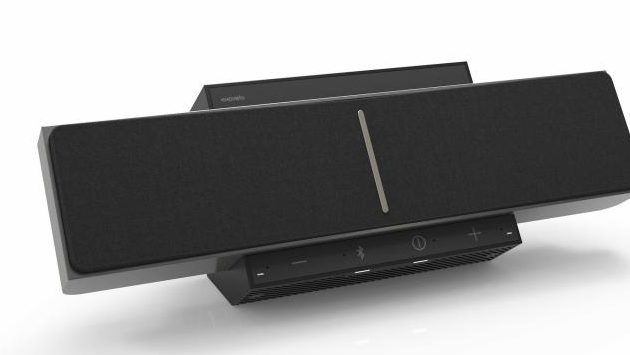

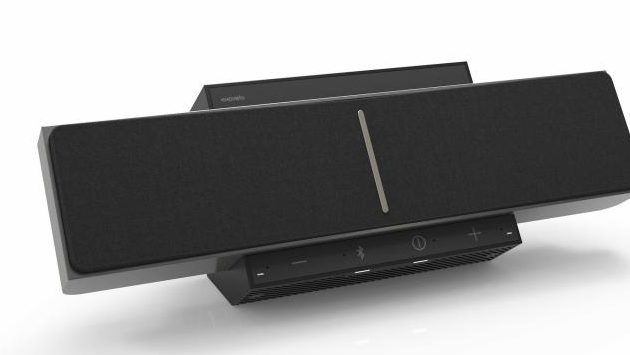

Company Develops ‘Sound Beaming’ to Enable Digital Listening in Your Own Sound Bubble – A Cone of Near-Silence (2025-08-08T13:25:00+05:30)

Noveto An Israeli tech startup has developed a speaker system that creates a “sound bubble”—essentially meaning you get all the privacy of headphones without the physical requirement of wearing them. The truly sci-fi tech uses ultrasonic waves beamed into pockets next to your ears. The aptly named “SoundBeaming” technology means you hear the noise coming from behind, below, and around you, while others nothing at all. If you’re still not clear about what Noveto’s product does, even CEO Christophe Ramstein finds it hard to put the concept into words. “The brain doesn’t understand what it doesn’t know,” he said in a statement. “I was thinking… is [SoundBeaming] the same with headphones?’ No, because I… have the freedom of doing what I want to do. And I have these sounds playing in my head as there would be something happening here, which is difficult to explain because we have no reference for that,” he said. The applications of this product are nearly endless, from being able to listen in on conference calls and other work-related audio without disturbing your neighbors, to removing the risk of losing, tripping on the cord of, or damaging, expensive audio headsets or earbuds.  Noveto Noveto3D facial mapping software continuously keeps track of where your head and ears are, and the speakers actually adjust where they must beam the soundwaves. This means that for those not remaining in a fixed position, for instance on exercise bikes, at L-shaped desks, or in the kitchen—the sound still follows you wherever you go. However, unlike headphones, the sounds of your environment can still be heard. If someone calls your name from another room, it’s clearly audible. “Most people just say, ‘Wow, I really don’t believe it,’” SoundBeamer Product Manager Ayana Wallwater said from the Noveto offices in Tel Aviv. “This is what we dream of,” she added “A world where we get the sound you want. You don’t need to disturb others and others don’t get disturbed by your sound. But you can still interact with them. Noveto’s speaker system, though already launched, isn’t available now, but the company plans on releasing a smaller version by Christmas 2021. Company Develops ‘Sound Beaming’ to Enable Digital Listening in Your Own Sound Bubble – A Cone of Near-Silence

|

Company Develops ‘Sound Beaming’ to Enable Digital Listening in Your Own Sound Bubble – A Cone of Near-Silence (2025-06-26T11:01:00+05:30)

An Israeli tech startup has developed a speaker system that creates a “sound bubble”—essentially meaning you get all the privacy of headphones without the physical requirement of wearing them. The truly sci-fi tech uses ultrasonic waves beamed into pockets next to your ears. The aptly named “SoundBeaming” technology means you hear the noise coming from behind, below, and around you, while others nothing at all. If you’re still not clear about what Noveto’s product does, even CEO Christophe Ramstein finds it hard to put the concept into words. “The brain doesn’t understand what it doesn’t know,” he said in a statement. “I was thinking… is [SoundBeaming] the same with headphones?’ No, because I… have the freedom of doing what I want to do. And I have these sounds playing in my head as there would be something happening here, which is difficult to explain because we have no reference for that,” he said. The applications of this product are nearly endless, from being able to listen in on conference calls and other work-related audio without disturbing your neighbors, to removing the risk of losing, tripping on the cord of, or damaging, expensive audio headsets or earbuds.  Noveto Noveto3D facial mapping software continuously keeps track of where your head and ears are, and the speakers actually adjust where they must beam the soundwaves. This means that for those not remaining in a fixed position, for instance on exercise bikes, at L-shaped desks, or in the kitchen—the sound still follows you wherever you go. However, unlike headphones, the sounds of your environment can still be heard. If someone calls your name from another room, it’s clearly audible. “Most people just say, ‘Wow, I really don’t believe it,’” SoundBeamer Product Manager Ayana Wallwater said from the Noveto offices in Tel Aviv. “This is what we dream of,” she added “A world where we get the sound you want. You don’t need to disturb others and others don’t get disturbed by your sound. But you can still interact with them. Noveto’s speaker system, though already launched, isn’t available now, but the company plans on releasing a smaller version by Christmas 2021.Company Develops ‘Sound Beaming’ to Enable Digital Listening in Your Own Sound Bubble – A Cone of Near-Silence |

Most of us will leave behind a large ‘digital legacy’ when we die. Here’s how to plan what happens to it (2025-06-05T13:16:00+05:30)

Bjorn Nansen, The University of MelbourneImagine you are planning the funeral music for a loved one who has died. You can’t remember their favourite song, so you try to login to their Spotify account. Then you realise the account login is inaccessible, and with it has gone their personal history of Spotify playlists, annual “wrapped” analytics, and liked songs curated to reflect their taste, memories, and identity. We tend to think about inheritance in physical terms: money, property, personal belongings. But the vast volume of digital stuff we accumulate in life and leave behind in death is now just as important – and this “digital legacy” is probably more meaningful. Digital legacies are increasingly complex and evolving. They include now-familiar items such as social media and banking accounts, along with our stored photos, videos and messages. But they also encompass virtual currencies, behavioural tracking data, and even AI-generated avatars. This digital data is not only fundamental to our online identities in life, but to our inheritance in death. So how can we properly plan for what happens to it? A window into our livesDigital legacy is commonly classified into two categories: digital assets and digital presence. Digital assets include items with economic value. For example, domain names, financial accounts, monetised social media, online businesses, virtual currencies, digital goods, and personal digital IP. Access to these is spread across platforms, hidden behind passwords or restricted by privacy laws. Digital presence includes content with no monetary value. However, it may have great personal significance. For example, our photos and videos, social media profiles, email or chat threads, and other content archived in cloud or platform services. There is also data that might not seem like content. It may not even seem to belong to us. This includes analytics data such as health and wellness app tracking data. It also includes behavioural data such as location, search or viewing history collected from platforms such as Google, Netflix and Spotify. This data reveals patterns in our preferences, passions, and daily life that can hold intimate meaning. For example, knowing the music a loved one listened to on the day they died. Digital remains now also include scheduled posthumous messages or AI-generated avatars. All of this raises both practical and ethical questions about identity, privacy, and corporate power over our digital afterlives. Who has the right to access, delete, or transform this data? Planning for your digital remains

Just as we prepare wills for physical possessions, we need to plan for our digital remains. Without clear instructions, important digital data may be lost and inaccessible to our loved ones. In 2017, I helped develop key recommendations for planning your digital legacy. These include:

What if your loved one left no plan?These steps may sound uncontroversial. But digital wills remain uncommon. And without them, managing someone’s digital legacy can be fraught with legal and technical barriers. Platform terms of service and privacy rules often prevent access by anyone other than the account holder. They can also require official documentation such as a death certificate before granting limited access to download or close an account. In such instances, gaining access will probably only be possible through imperfect workarounds, such as searching online for traces of someone’s digital life, attempting to use account recovery tools, or scouring personal documents for login information. The need for better standardsCurrent platform policies have clear limitations for handling digital legacies. For example, policies are inconsistent. They are also typically limited to memorialising or deleting accounts. With no unified framework, service providers often prioritise data privacy over family access. Current tools prioritise visible content such as profiles or posts. However, they exclude less visible yet equally valuable (and often more meaningful) behavioural data such as listening habits. Problems can also arise when data is removed from its original platform. For example, photos from Facebook can lose their social and relational meaning without their associated comment threads, reactions, or interactivity. Meanwhile, emerging uses of posthumous data, especially AI-generated avatars, raise urgent issues about digital personhood, ownership, and possible harms. These “digital remains” may be stored indefinitely on commercial servers without standard protocols for curation or user rights. The result is a growing tension between personal ownership and corporate control. This makes digital legacy not only a matter of individual concern but one of digital governance. Standards Australia and the New South Wales Law Reform Commission have recognised this. Both organisations are seeking consultation to develop frameworks that address inconsistencies in platform standards and user access. Managing our digital legacies demands more than practical foresight. It compels critical reflection on the infrastructures and values that shape our online afterlives. Bjorn Nansen, Associate Professor, School of Computing and Information Systems, The University of Melbourne This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

What is a ‘smart city’ and why should we care? It’s not just a buzzword (2025-05-12T11:41:00+05:30)

|

More than half of the world’s population currently lives in cities and this share is expected to rise to nearly 70% by 2050.

It’s no wonder “smart cities” have become a buzzword in urban planning, politics and tech circles, and even media. The phrase conjures images of self-driving buses, traffic lights controlled by artificial intelligence (AI) and buildings that manage their own energy use. But for all the attention the term receives, it’s not clear what actually makes a city smart. Is it about the number of sensors installed? The speed of the internet? The presence of a digital dashboard at the town hall? Governments regularly speak of future-ready cities and the promise of “digital transformation”. But when the term “smart city” is used in policy documents or on the campaign trail, it often lacks clarity. Over the past two decades, governments around the world have poured billions into smart city initiatives, often with more ambition than clarity. The result has been a patchwork of projects: some genuinely transformative, others flashy but shallow. So, what does it really mean for a city to be smart? And how can technology solve real urban problems, not just create new ones? What is a smart city, then?The term “smart city” has been applied to a wide range of urban technologies and initiatives – from traffic sensors and smart meters to autonomous vehicles and energy-efficient building systems. But a consistent, working definition remains elusive. In academic and policy circles, one widely accepted view is that a smart city is one where technology is used to enhance key urban outcomes: liveability, sustainability, social equity and, ultimately, people’s quality of life. What matters here is whether the application of technology leads to measurable improvements in the way people live, move and interact with the city around them. By that standard, many “smart city” initiatives fall short, not because the tools don’t exist, but because the focus is often on visibility and symbolic infrastructure rather than impact. This could be features like high-tech digital kiosks in public spaces that are visibly modern and offer some use and value, but do little to address core urban challenges. The reality of urban governance – messy, decentralised, often constrained – is a long way from the seamless dashboards and simulations often promised in promotional material. But there is a way to help join together the various aspects of city living, with the help of “digital twins”. Digital twin (of?) citiesMuch of the early focus on smart cities revolved around individual technologies: installing sensors, launching apps or creating control centres. But these tools often worked in isolation and offered limited insight into how the city functioned as a whole. City digital twins represent a shift in approach. Instead of layering technology onto existing systems, a city digital twin creates a virtual replica of those systems. It links real-time data across transport, energy, infrastructure and the environment. It’s a kind of living, evolving model of the city that changes as the real city changes. This enables planners and policymakers to test decisions before making them. They can simulate the impact of a new road, assess the risk of flooding in a changing climate or compare the outcomes of different zoning options. Used in this way, digital twins support decisions that are better informed, more responsive, and more in tune with how cities actually work. Not all digital twins operate at the same level. Some offer little more than 3D visualisations, while others bring in real-time data and support complex scenario testing. The most advanced ones don’t just simulate the city, but interact with it. Where it’s workingTo manage urban change, some cities are already using digital twins to support long-term planning and day-to-day decision-making – and not just as add-ons. In Singapore, the Virtual Singapore project is one of the most advanced city-scale digital twins in the world. It integrates high-resolution 3D models of Singapore with real-time and historical data from across the city. The platform has been used by government agencies to model energy consumption, assess climate and air flow impacts of new buildings, manage underground infrastructure, and explore zoning options based on risks like flooding in a highly constrained urban environment. In Helsinki, the Kalasatama digital twin has been used to evaluate solar energy potential, conduct wind simulations and plan building orientations. It has also been integrated into public engagement processes: the OpenCities Planner platform lets residents explore proposed developments and offer feedback before construction begins. We need a smarter conversation about smart citiesIf smart cities are going to matter, they must do more than sound and look good. They need to solve real problems, improve people’s lives and protect the privacy and integrity of the data they collect. That includes being built with strong safeguards against cyber threats. A connected city should not be a more vulnerable city. The term smart city has always been slippery – more aspiration than definition. That ambiguity makes it hard to measure whether, or how, a city becomes smart. But one thing is clear: being smart doesn’t mean flooding citizens with apps and screens, or wrapping public life in flashy tech. The smartest cities might not even feel digital on the surface. They would work quietly in the background, gather only the data they need, coordinate it well and use it to make citizens’ life safer, fairer and more efficient. Milad Haghani, Associate Professor & Principal Fellow in Urban Risk & Resilience, The University of Melbourne; Abbas Rajabifard, Professor in Geomatics and SDI, The University of Melbourne, and Benny Chen, Senior Research Fellow, Infrastructure Engineering, The University of Melbourne This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Digital mindfulness could help reduce the effects of technostress at work (2024-03-26T11:24:00+05:30)

|

Technology-related stress, overload and anxiety are common problems in today’s workplace, potentially leading to higher burnout and poorer health. Many of these issues are likely to have increased since remote working became much more widespread following the pandemic. In 2022, along with colleagues at the University of Nottingham, I conducted a review of the academic literature on the downsides of digital working. We looked at nearly 200 studies from over the past decade, which revealed extensive evidence of negative health impacts of technostress and related “dark side of digital workplace” effects. Building on that research, our next study, published in 2024, investigated whether mindfulness and digital confidence – the ability to apply existing digital skills to new devices, apps and platforms – might help reduce these negative effects. We found that being more confident and mindful when using technology could help protect the health of digital workers. Mindfulness is a technique to develop an nonjudgmental awareness of one’s feelings, thoughts and surroundings in the present moment. It can help some people to avoid negative habits and responses by learning to observe their thoughts and emotions and tune in to the breath and body as an anchor. Becoming aware of habitual reactions In this way can help us to respond in a calmer, more effective manner. Our latest study adds to evidence collected through many decades of workplace mindfulness research, which has demonstrated its potential to reduce stress and anxiety among workers, as well as promoting better mental health and improving work engagement. While our research did not investigate specific mindfulness techniques, our interview participants talked about ways that being mindful helped them to reduce stress in the digital workplace. This could be as simple as pausing for a few deep breaths or stepping away from the technology for a short period. Checking in with their own mental, emotional and physical state while working digitally was also something that people said really helped them. Participants with higher levels of mindfulness tended to be less overwhelmed by technology. They talked about avoiding multitasking online – for example, reading emails while on a video call – as well as establishing clear boundaries around its use, such as only using technology at certain times of the day. It is worth noting that some workers were uneasy about taking time to disconnect, noting that they feared being seen as slacking or falling behind. Overall, workers who were more confident with technology experienced less anxiety. And those who were more mindful appeared better protected from the negative aspects of digital working. Our results suggest that although digital mindfulness and confidence are both important for employee wellbeing, ultimately, mindfulness is more effective than confidence with technology in protecting against technostress. Change perceptions to improve wellbeing: In our analysis we explore the idea, based on previous studies, that mindfulness can help reduce anxiety by altering employees’ perceptions of digital stressors. For example, researchers from the University of Turin in 2019 found that higher mindfulness among teachers was associated with a more positive workload stress appraisal and lower rates of subsequent burnout. In our study, we found that digital workers who were more mindfully and digitally confident appeared to have a greater sense of agency when working digitally. They were also better equipped to change their digital habits for the better. These changes involved setting boundaries by implementing rules for how and when to engage in the digital workplace. For example, turning off notifications, batching email or shutting down devices at the end of the working day. Some participants also used short mindful practices to regulate their engagement with technology and take care of physical and mental health while working digitally. Beneficial activities included taking a short break from technology, going for a walk or making a cup of tea. Reflection is key to healthy digital habits: To help employees thrive during the ongoing digital transformation of the workplace, organisations should consider ways to support staff with digital skills and mindful practices. Otherwise, they risk workers suffering further negative effects. Conducting this research made our team think about our own digital practices and identify areas for change. For instance, being setting clearer boundaries around reading and responding to emails outside of work hours and taking more pauses while working digitally. There are opportunities for all of us to grow our own skills in these areas, for example by engaging with training or self-learning to raise our digital competencies for work and learn some basic mindfulness practices. Reflecting on what is and isn’t working in your digital work day can be a great place to start in fostering healthy digital work habits.  Elizabeth Marsh, PhD Candidate, employee technostress and the potential of mindfulness, School of Psychology, University of Nottingham This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. Elizabeth Marsh, PhD Candidate, employee technostress and the potential of mindfulness, School of Psychology, University of Nottingham This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

Nicole Kidman, face of airline campaign (2016-05-01T23:14:00+05:30)

|

ICICI Bank launches digital locker (2016-01-21T15:52:00+05:30)

Mydigitalfc, By PTI Aug 18 2015 , New Delhi, ICICI Bank today launched the first of its kind fully automated digital locker which would be available to customers even on weekends and post banking hours. Named 'Smart Vault', the locker is equipped with multi-layer security system, including biometric and PIN authentication and debit cards, among others. Customers can access it without any intervention by the branch staff, ICICI Bank said in a statement. "Through the Smart Vault, we bring a very different, much more convenient, state of art branch experience to the customers," ICICI Bank MD and CEO Chanda Kochhar said after its launch here. The 'Smart Vault' is an example of 'Make In India' programme as it has been designed and manufactured by Indian partners, she said. "The vault uses robotic technology to access the lockers from the safe vault and enables customers to access their lockers at any time of their preference," the statement issued by ICICI Bank, country's largest private sector lender, said. Asked about charges of the digital locker, Kochhar said: "The lockers are of two-three different sizes and charges would depend on that. Also, the locker charges in a city would vary depending on the real estate cost." Launched in Delhi, Kochhar said the bank would replicate this digital locker facility to a much larger scale in the days to come. Source: mydigitalfc.com

|